Elegance In Black

By Christian Chensvold

Los Angeles Times, January 19, 2005

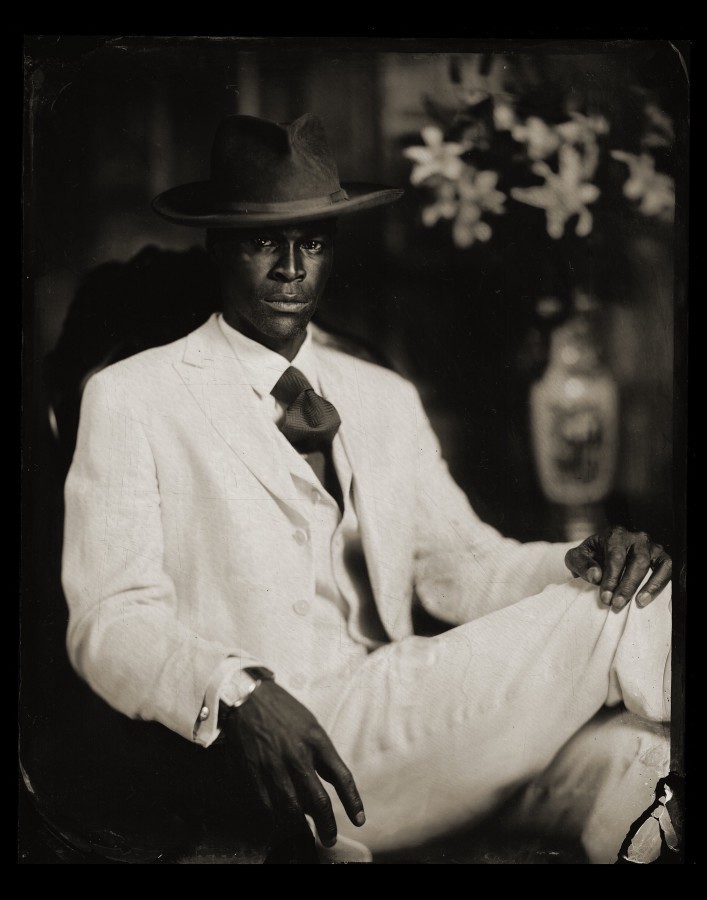

Michael Henry Adams’ epiphany came in the quiet stillness of the Akron Public Library. Hanging on the wall were photographs of the Harlem Renaissance era by James Van Der Zee. “There were images of blacks who were every bit as polished and elegant as Clark Gable or Cary Grant,” Adams says. “That was a revelation for me, and also a justification. Before that, I would have felt that to identify with the style of Fred Astaire would have not been something that reflected blackness.”

In an age when T-shirts and jeans are the closest thing to world democracy, true style icons are rare. But in October, Esquire magazine crowned OutKast frontman Andre 3000 as the best-dressed man in the world. With urban street wear firmly lodged in the mainstream, Andre 3000’s penchant for hats, vests and Savile Row tailoring suddenly appeared less a personal idiosyncrasy than the result of a man who had found a kind of sartorial enlightenment.

An increasing number of African American men, in fact, are embracing classic gentlemen’s attire, riding the forefront of fashion’s return to luxury and timeless classics while adopting a mode of expression that subverts stereotypes of black style. In contrast to the mostly white metrosexual phenomenon — a fop-fest of manicures, grooming gewgaws and trendy designer wear — today’s renaissance of black elegance seems a striving for dignity and good taste in an era not exactly known for either.

Recently at Macy’s Passport, the annual charity event held in Santa Monica, the best-dressed men — clad in tailored trousers, velvet blazers, ascots and pocket squares — were black. Durand Guion, Macy’s West fashion director, styled the event, which featured African American models in silk pajamas and velvet smoking jackets, a look that less than a decade ago was parodied by Charles Barkley in a series of Right Guard commercials. “We’ve been as casual as can be for so long that a new, big fashion trend is on the horizon,” Guion says. “And it’s definitely about dressing up. Young African American men are jumping on the trend quickly, because at the end of the day, it’s something new and a way to get attention.” Classic gentlemen’s attire is also aspirational, Guion says, a subtle alternative to the “bling bling” that rappers and other pop stars have been known to don when trying to look elegant. “There’s a whole idea of reaching the next level, and fashion is a quick assessment of whether you’ve done that or not.”

Classic finery contrasts with traditional “urban suiting” like stripes against plaid. The new movement often involves ascots, pocket squares, and bow ties. The bright, baggy suits and matching accessories of such brands as Stacy Adams and entertainer Steve Harvey’s eponymous collection are beginning to seem cliche to many younger blacks. “For Harvey’s generation, a six-button cranberry suit with matching hat was aspirational,” Guion says, “but it’s not anymore.”

Adams, a 48-year-old architectural historian and author of “Style and Grace: African-Americans at Home,” finds it amusing that young men would want to dress like him. Since leaving Ohio for Harlem, the author has dressed in classic boulevardier style: dark suits, wing-collared shirts from Brooks Brothers, bowler hats in the winter and straw boaters in the summer. On the street, his nonconformity earns equal measures of admiration and derision: Young people call him “Poindexter” or “Mr. Magoo.”

Adams takes the jeers in stride. “The norm of casualness at all costs makes adapting correct standards of the past subversive and an act of defiance,” he says, adding, “African Americans have been involved in notions of style and taste since the very beginning.”

That beginning may have been in the shackles of oppression, but it grew into a rich tapestry of black male elegance, including Duke Ellington, W.E.B. DuBois, Langston Hughes and the tap-dancing duo the Nicholas Brothers, who would leap from the bandstand, their tailcoats flapping like wings.

“Within African American culture there is a move to stay ahead of cliches, stereotypes and ideas about black people that seem fixed,” says Monica Miller, an English professor at Barnard College, who is black. “You’re given an image of yourself, but you flip it to your own advantage, with an element of playful confusion,” says Miller, who is writing a book titled “Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism in the Atlantic Diaspora,” which examines black male style over the last two centuries.

The most visible embodiment of playful confusion is Fonzworth Bentley. Né Derek Watkins, the 30-year-old bow-tied and bicoastal Bentley, who keeps a flat in West Hollywood, first rose to the public eye as the personal assistant of P. Diddy. Saying we live in a “golden age of disrespect,” Bentley is the panjandrum of the hip-hop community’s “gentlemen’s movement.”

A social reformer with a corporate sponsorship, Bentley tours nightclubs giving “gentlemen’s makeovers” to youths in baggy track suits — Courvoisier, whose U.S. consumer base is predominantly African American, picks up the tab. With his omnipresent carved ostrich-handled umbrella — a gentleman’s accessory or pretentious accouterment depending on how you read it — Bentley recently graced the inaugural cover of Uptown, a new lifestyle magazine declaring a return of the Harlem gentleman.

With his flamboyant sobriquet and penchant for photo-op poses that seem a cross between Billy Dee Williams and Pee Wee Herman, it remains unclear if Bentley is an authentic social reformer or simply a dapper charlatan destined to 15 minutes of chauffeur-driven fame. “I’m intrigued, but I’m having a difficult time reading him,” Miller says.

Bentley says he is out to inspire young blacks and believes proper dress encourages a more civil society. “I want to bring about change,” he says. But perhaps those most inspired by him are the elderly, who still recall the world of elegance captured by Van Der Zee’s photography. “I get so many compliments from older black people,” Bentley says, “who say, ‘I love what you’re doing. It makes me proud.’ ”

And where there’s a trend, there’s money to be had: Andre 3000’s clothing line, AndreBenjamin is set to bow in the spring. Bentley is developing a line of umbrellas for Bloomingdale’s and has signed publishing, television and recording deals.

Waraire Boswell sits in the lounge of Chateau Marmont, his lanky 6-foot-6 frame reposing on a leather sofa in svelte nonchalance. Clad in a navy bespoke suit of his own design, he looks as if he owns the place. Boswell, 28, is a Los Angeles-based fashion designer determined to foist classic finery on a city that seems to think haberdashery is some sort of communicable disease.

Classic-with-a-twist is fashion’s current muse, and Boswell embodies it to perfection: His suit features mismatching gold buttons and creative contrast stitching, his socks are rainbow striped, his canary-checked shirt would meet the approval of the Great Gatsby and his yellow tie is peppered with butterflies.

As for his billowy pocket square, it matches not the fabric of his tie, which would be gauche, but his shirt — a whimsical beau geste.

Unable to find stylish clothes in his size, Boswell launched his eponymous clothing line in 2001. Since then, he’s outfitted Andre 3000 in several plaid suits registering somewhere between classic and loud, and sells his line at boutiques such as Lisa Kline and Fred Segal. Barely able to keep up with production demand, Boswell is already preparing to be the next fashion sovereign: His business card reads “patrician.” Says the designer, “People ask me if that means I take care of pets.”

His taste for gentlemen’s finery represents a quest for distinction and a war against platitude. “It’s all about presentation,” Boswell says. “If I’m in jeans and a T-shirt, people would think, ‘He’s just a regular guy.’ But when you look good, the reaction is, ‘I need to find out what makes this guy tick.'”

The old adage that clothes make the man may be even more relevant to the African American experience. “Blacks know the power of dressing well and how it levels the playing field,” says Lloyd Boston, whose 1998 book, “Men of Color,” is a lavish compendium of black male style. “Today’s black trendsetters are looking to the past for something young and fresh. The men of the Harlem Renaissance didn’t have a lot of money, but they created a whole community around looking sharp. Men of color love to be preening peacocks,” says Boston, who is black.

The renaissance of high style represents a maturation of the hip-hop community, professor Miller says. Men such as Jay-Z and P. Diddy have risen from rappers to corporate moguls and, for them, classic dress symbolizes arrival. She also notes two distinct strains in the history of black style: one a rebellion against mainstream mores — expressed in zoot suits of the 1940s and the urban street wear of today — the other a desire to demonstrate mastery of conventional standards of dress.

If there’s one sartorial symbol of the modern gentleman, it is the antiquarian ascot. Suddenly, a paisley swath of silk draped around the neck is an act of chic defiance. San Francisco-based graphic designer by day and tango dancer by night Count Glover, 33, has sported ascots, French cuffs and tailored suits for years. As a Marine on shore leave, he would get measured for custom suits, and his penchant for spiffy civvies earned him much teasing from his fellow Marines.

Glover welcomes more socially acceptable clothing choices for black men but doubts society can turn back the sartorial clock. “Nothing’s going to be rebuilt, but more people will have the option to do what they like to do. You won’t have the pressure of only wearing Sean John or Fubu.”

Adams agrees: “Elegance takes more effort than most people are willing to bother with, which is part of its charm, but I can’t see it becoming a mass movement.”

But perhaps widespread revolution is not the point. “Now, thanks to these young men like Fonzworth Bentley,” Adams adds, “blacks have more options about how to express themselves in terms of style — and that’s a good thing.”

hi great post i would like to just try to encourage people to read up on the harlem renaissance and find out about the great cultures set during that period.