All dandies have their rituals. On a typical morning in the years just after the Second World War, Osbert Lancaster would rise about nine to the Times and Daily Express, a quiet bath, and a light breakfast of coffee and toast. Clad in one of the old, ink-stained Oriental robes he had picked up in the East, and which had earned him the household nickname of Pasha, Osbert would then sit down in his library and, wreathed in cigarette smoke, begin to work.

Usually he was illustrating: either for friends’ books or his own. Architecture was his favored subject. At about noon he would rise from his desk and, accompanied by a single dry martini, he would dress. This usually took some time, though his clothes were simple: a two-piece suit, often chalk-striped and sometimes double-breasted; colorful tie, handkerchief, carnation and dark shoes. On his way out the door, he’d put on a hat with the brim turned up all the way around. Thus attired, he would take up his stick and walk to one of his clubs — Brooks, Beefsteak or the Garrick — for lunch and to glean the gossip he would use later in the afternoon. Sometimes he would look in at the foreign office in Whitehall. At about four o’clock Osbert would arrive at his desk in the bustling newsroom of the London Daily Express in Fleet Street. There he would light a Turkish cigarette and share more gossip — local news was his term for it. Then he would wander around the floor, sighing that he simply didn’t have a clue what to do next. Finally, as his deadline loomed near, he would go back to his desk and, in 20 minutes, draw a single-panel comic, one of the 10,000 “pocket cartoons” that would make him notorious in London over a career spanning half a century. These cartoons, which featured a vast cast of regular and semi-regular characters, held up a fun-house mirror to the fads, follies and foibles of the day, skewering shibboleths with surgical accuracy.

Osbert Lancaster stands among the most prominent of the minor dandies. These are men who, through dint of superb personal style, effervescent social skills and, in some cases, a little artistic or literary talent, get noticed, but who cannot be said to stand among the highest in the dandy hierarchy. Max Beerbohm is the borderline between the mighty and the minor. He is either the least great of the great dandies for his writings on dandyism, or the greatest of the minor dandies (not too original, sartorially speaking). The majority of the minor dandies never wrote about dandyism, and many never felt the desire to approach the subject, even in conversation. All were impeccable, and some even original. Riding the high end near Max we might find the Duke of Windsor, Cecil Beaton and Noel Coward, and beneath them someone like Bunny Roger, as well as the current Prince of Wales. The aviator, Alberto-Santos Dumont, surely lived in this society. Tom Wolfe is in there somewhere, dressed to the nines, or perhaps overdressed to the eighteens. Most of the minor dandies are those unsung heroes of style who take the time each day to chisel out from their persons an ideal of manly elegance. They could be your dapper grandfather or idling uncle, or the man down at the insurance office who walks to work each morning in an immaculate suit, the chrysanthemum adorning his buttonhole reflected in the perfect sheen of his cap-toed shoes. In fact, Wolfe wrote a cameo of just such a minor-most dandy in his Bonfire of the Vanities: namely the court reporter who has the temerity to wear two-tones shoes in the courtroom, and who makes the penuriously paid cops feel like galumphing and unstylish schlubs in their cheap gumshoes.

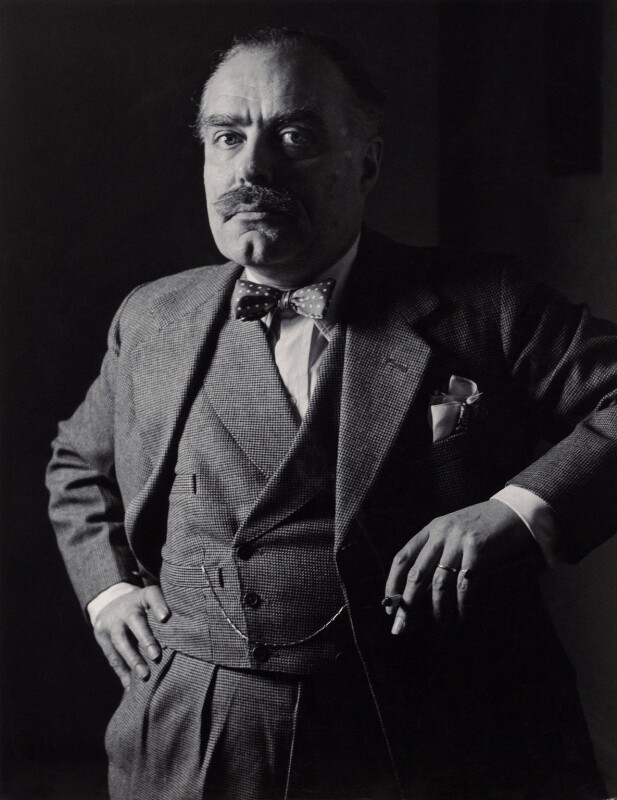

“Dandy” was what other people thought when they thought of Osbert Lancaster. He rarely made recourse to the term and never, as far as I know, used it to describe himself. Illustrative of his minor status is the fact I had never heard of him before stumbling across Richard Boston’s Osbert: A Portrait of Osbert Lancaster in a remaindered bookstore in Burbank, CA (surely a sad resting place for any beau). The cover included a photograph of an elder gentleman bearing a striking resemblance to Beerbohm in his Rapallo years, with a wiry gray mustache, high forehead and heavily lidded eyes. He wore the dark, double-breasted jacket and colorful tie described above. His hand was on his cheek, a pencil between his fingers; his slender wrist disappearing into a generous cuff secured by a link that held a dark, gleaming stone. Curious, I took the book down, leafed through it and landed on the following passage: “The dandy is obliged to make whatever he does look easy. Many hours in front of the mirror were required to produce the precise casual elegance of Beau Brummell’s cravat.”

Osbert Lancaster was born in 1908, near the end of the Edwardian era, and carried throughout his life the memory of those final, happy days before Europe’s first Armageddon. He was the last of the last of the Edwardians. (His first name, Osbert, is a derivation of Albert, the Christian name of Edward VII.) According to Boston’s biography — from which the bulk of the facts in this dispatch have been shamelessly cribbed — the young Osbert was an unwilling schoolboy at Charterhouse, where the headmaster’s final report praised him as “irretrievably gauche” and “a sad disappointment.” For Osbert the feeling was mutual: He was already drawing at this time — the officials at Charterhouse coming in for many an illustrated drubbing — and already in the active style full of movement that would mark his future work.

Osbert’s first move after being admitted to Lincoln College, Oxford, was to grow the distinguished, just-shy-of-Stalinesque mustache that would adorn his upper lip for the rest of his life, and which was quite contrary to the prevailing fashion among the university’s effete young arbiters of taste. His contemporaries at Oxford include a who’s who of 20th-century aesthetes, dandies and literati: Allan Pryce-Jones, Beverly Nichols, Cecil Day-Lewis, Cyril Connolly, Evelyn Waugh, Harold Acton, Randolph Churchill (Winston’s boy, whom Osbert described as “without exception the best-looking man I’ve ever seen”), and Robert Byron. During his college years Osbert primarily ran with the aesthetes as opposed to the games-mad hearties. Yet unlike many of his fellow artistic and literary friends he wasn’t gay. Nor was he attracted, like Waugh and others, to Catholicism. With drawing-room Marxism and other lefty political poses he would have no truck; likewise with the far right. He was uniquely Osbert, and that had already come to mean a balanced mind with a sense of proportion in a modest conservatism.

Boston’s book includes one of Osbert’s later cartoons depicting Oxford in the ’20s. It is archetypical Lancaster, being a single scene with much going on. Three windows and the doorway of a Georgian townhouse are shown. Through the panes of the upper floors the viewer glimpses a party of men drinking and smoking, chatting and arguing. Each figure is distinct in dress, manner, expression and deportment — each perhaps a caricature of one of Osbert’s contemporaries. Outside, in the street below, is a distinctly Wildean figure (Harold Acton, Waugh’s role model for Anthony Blanche perhaps?) leading a distinctly Lord Alfred Douglas-type figure to the townhouse’s front door. Glaring at this pair out through the window on the lower floor is a scowling matron. Whether she disapproves of this couple or merely the noise from the party above is uncertain. It’s the kind of ambiguity one finds, and relishes, throughout Osbert’s work.

“Many of the aesthetes who left Oxford in the 1920s,” writes Boston, “found that their long and expensive education had not equipped them well for earning a living in a congenial manner.” Osbert was in a quandary about what to do after university. His parents were well enough off in an Enoch Soames “he has an income” sort of way, but not they were not what you would call rich. Osbert needed to do something. He could go into trade (anathema to his Oxford circle), go to the prep schools and teach, or go abroad like so many of the artists and writers he knew. Osbert decided, after an abortive try at the bar, to stay at home, study what he knew (London and the English), and express what he learned through art and letters. He enrolled in the Slade School and threw himself into drawing and stage design. At Slade Osbert met Karen Harris, then just 17 (he was 23). He married her two years later in 1933. Their wedding photo shows the couple standing in front of a mantle — Karen all but drapped on Osbert’s arm — a pretty, serious woman with the slinky posture of a flapper. Osbert wears a typical morning suit of the period with striped trousers and a cravat tucked into his waistcoat. Theirs was a long marriage, happy in a very English sort of way, lasting until Karen died in 1964.

After Slade, Osbert’s career as a man of arts and letters began in earnest. He did just about everything, from illustrating Christmas cards and creating posters to murals and occasionally exhibiting the odd painting. It about this time he began illustrating books, such as John Betjeman’s An Oxford Community Chest, writing and illustrating his own (Progress at Pelvis Bay and others), and working for the Architectural Review, where he wrote everything from captions to features. He often served as a traditionalist foil to other critics’ rigid modernism. Of Lancaster’s writing style at the Architectural Review, Boston writes, somewhat loquaciously, “The cadences are classically balanced, the tone is one of dandyish superiority that fully exploits the comic potential of taking a reductive, Gulliver’s-eye view of the absurdly miniscule activities and aspirations of the Lilliputians.”

Osbert’s sartorial style also crystallized during the ’30s. Like many of the more innovative dandies before him, Osbert’s style was decided not only by what he chose wear but what he cast off. “I wear everything I was not allowed to wear at Charterhouse. We were not allowed jackets with vents, shirts with attached collars, or less than three buttons to a jacket,” he once said. “As soon as I left school, I had all my suits made up with two-button jackets.” He claimed to have set the fashion for attached collars and pink shirts. “My shirtmaker was appalled,” he remembered. And he discarded vests — he said that central heating had made them unnecessary — and the boots that his mother insisted “were so good for my ankles.” He was not above a bit of sartorial daring now and then and claimed to be among the first to wear white dinner jackets. It’s probable that Noel Coward was really among the first, but Osbert was no doubt the first among his set and class, which is what counts. Osbert may have been a shade more casual a dandy than his predecessors — which is also, of course, very like many of his dandy predecessors. But he insisted on certain standards, such as dinner jackets for evening, saying, “I can’t see the point of saying ‘don’t dress, just put on a dark suit.’ If you are going to change, you might as well do it properly.”

Despite the depression, the mid-1930s were good times for the Lancasters, all the way up until the time the Germans invaded Poland. Osbert wasn’t exactly the military type, but he managed to do his part and with considerable aplomb. He joined the Diplomatic Service and was sent to the British Embassy in Athens after British and Greek forces forced the Nazis out, only to be caught in the middle of one of the least pleasant civil wars of the 20th century. Here he worked with Harold Macmillan, among other notables. Caught between the various trigger-happy factions, the embassy was all but used by snipers for target practice. The ricochet of bullets served as accompaniment to each day’s dissonant aria of diplomacy.

After the war, Osbert returned to London and settled into that pattern of life that would continue to make him such a quiet social, creative and commercial success. He continued creating his pocket cartoons, writing and illustrating his own books and illustrating those of his friends. In addition he gave lectures, went often to his tailor (Thresher & Glenny), appeared occasionally on BBC television, traveled to Italy (to see Max Beerbohm), as well as other places, painted murals for commercial buildings, designed costumes and sets for opera, ballet and theatre, and of course kept up with the gossip at his clubs and rarely turned down an invitation to a party. He was knighted in 1975, the only cartoonist ever to be thus honored. He died in 1986, aged 77.

Though prolific, Osbert was not one of the great artists or men of letters of his time. He does not share a gallery wall with Picasso or a shelf space with Hemmingway. Nor would he, I think, wish to. He was Osbert, and that was enough. He was, as Lord David Cecil said of Max Beerbohm, “a demure, dandified figure” amused by contemplating the world and from time to time letting fall a whimsical comment upon it. To some Osbert was a merely man of the world and a clever wit whose work was only the trifling of a gifted amateur. Of these people, says Boston, “They must have been deceived by the dandy’s slight of hand which conceals the solid hard work that goes on behind the scenes.” — MICHAEL MATTIS

Image via National Portrait Gallery.

Great job, Michael.

What struck me were the parallels between Osbert and Max, especially that they both went to Charterhouse.

An excellent summary of the life of one of my heroes, a model for us! My favourite quote from Sir Osbert should be better known:

“The boredom occasioned by too much restraint is always preferrable to that produced by an uncontrolled enthusiasm for a pointless variety”

Brilliant. Thanks, Sprez!

-M

Sir Osbert is a much appreciated esthete whose wry sense of humour delights me when I am about to despair of the human race.

Sir Osbert is what dandyism should be about: quiet originality.

And for more on Osbert you can now visit the exhibition CARTOONS & CORONETS: THE GENIUS OF OSBERT LANCASTER at The Wallace Collection in London until 11 January 2009 or buy the delightful new book of the same name by fellow dandy, James Knox. The show marks Osbert’s centenary

and includes an extensive survey of his work as architectural satirist, illustrator, theatre designer and cartoonist. And a quick Google will reveal that he is perhaps not as forgotten as we first thought we press coverage in Vogue, The Telegraph, The Independent, The Guardian, The Times, Radio 4, The Spectator, Country Life, World of Interiors, BBC Homes & Antiques, Time Out and many more.

PLUS if that wasn’t enough – author of the book will be in-conversation with Martin Rowson on 28 October in London in the truly dandy setting of Miller’s Academy in Notting Hill. Best wishes, Jeanette