The decadent dandy has as his guidebook “Against Nature,” the “poisonous” yellow book redolent of incense that Lord Henry gives to Dorian, the catalyst for Wilde’s young hero’s descent into Avernus. But do fundamentalist dandies, those devotees of Brummell — possessors of a languid wit, connoisseurs of a fine cut (both sartorial and social), practitioners of “country washing,” and aficionados of elegant neckwear — have a similarly inspirational guide? Surprisingly, the answer may lie in a little book dedicated to the Brummellian task of tying one’s tie properly. And it comes from the unlikeliest of authors: two condensed-matter physicists at Cambridge University’s Cavendish Laboratory, Thomas Fink and Yong Mao. The physicists applied topology (a branch of geometry), Knot Theory and physics to certain assumed practical constraints (e.g. length of tie, size of knot), and determined that there are exactly 85 ways to tie a tie.

Fink and Mao expanded their initial research into a jeu d’esprit entitled “The 85 Ways To Tie a Tie.” The book includes a history of neckcloths; sprinkles throughout photographs of the famous sporting various knots (the last photo, in context, is particularly clever and witty); briefly summarizes the relationship among topology, Knot Theory, physics and tying tie knots; and relegates to the appendix the mathematical proof. The glory of the book is in its instructions. Attractive diagrams and the authors’ own simple and especially devised notation detail the sequence of moves for tying each of the 85 knots move-by-move. These directions are the clearest and most precise ever written. Twenty-five knots are accorded short essays, a few only a sentence long.

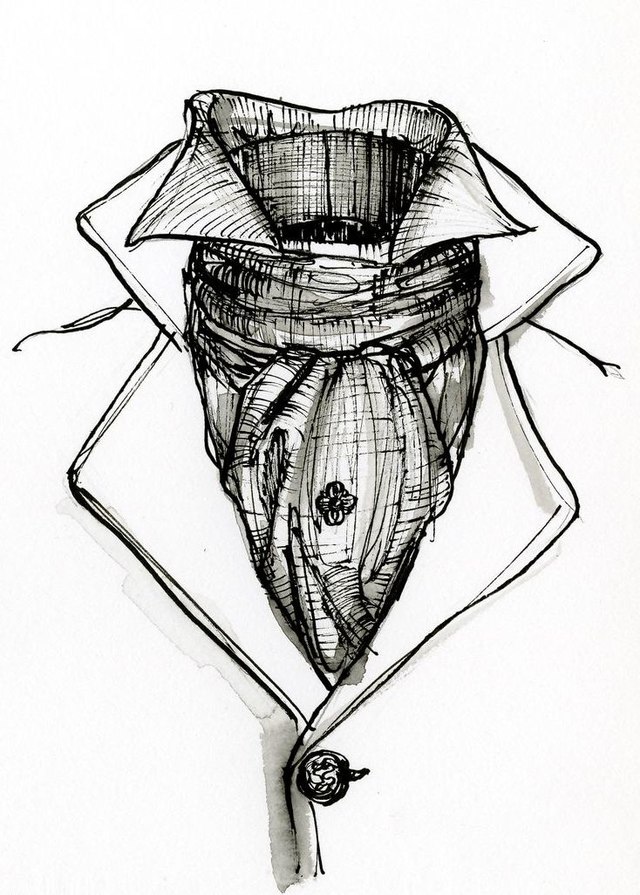

A dandy must perfect nineteen of the knots. Applying topological principles, the authors deem thirteen of the knots “aesthetic,” a designation without practical significance. The others are either indistinguishable iterations or simply too awful to sport. The knots run the gamut from casual to relaxed, formal to intricate. They range in size from three moves to nine. The shapes vary from a tapered, tunneled look to the triangular and bulbous. A number of knots begin with the tie inside-out around the neck — these are certainly the knots your father did not teach you. A delightful singularity is a variation of what the authors have dubbed “The Christensen,” which results in a cruciform design. It is very formal, intricate and elegant, and I chose this knot to go with my morning attire for my daughter’s wedding.

Dandies can be passionate about their knot preferences, but what is the best knot is intensely personal. There are four general considerations: It must harmonize with one’s face, the tie itself, the shirt collar, and the rest of one’s attire. In other words, the shape of the knot must accent good facial features and/or offset weak ones; the tie’s thickness, width, length and in some cases shape must be consistent with the knot; the knot must be proportionate to the length and spread of the shirt collar points (which in turn must flatter one’s face); and the formality or informality of the knot must match the rest of one’s attire. Learn the knots, experiment, and use one’s eye and educated sense of elegance to select, on any given occasion, one’s choice.

Brummell spent upwards of two hours each day arranging his cravat. He never left his digs until his cravat was perfect. A contemporary dandy should be content with no less. To paraphrase the creator of Dorian Gray — and Lord Henry — a well-tied tie is the first serious step in dandyism. — NICK WILLARD