My Dear Palmieri:

It is a rare and wonderful gift for a curmudgeon such as myself to receive the praise of youth. It’s nice to know my little column is read at all, but to be solicited for advice is a singular honor.

In your brief e-pistle you mentioned that you are about to start your studies at the University of Pennsylvania and that you will be studying English and perhaps taking a minor degree in psychology. Very well, a solid grounding in literature combined with some understanding of the motives that drive human behavior can be both enlightening and entertaining. Be sure not to take either too seriously, however, but treat each with the skepticism and humor it deserves. Besides, taking anything too seriously can lead to premature laugh lines, and those aren’t funny.

In anticipation of your arrival at university, you tell me that you have, “concocted a grand scheme with a dear friend… that involves the introduction of the dandy way of life to that of the University.” Furthermore you say: “Our manner of aestheticism and dress, we hope, preserves notions of Dandyism… into a frame of mind that promotes refinement of manners and elegance of speech.”

Hmm… a grand scheme? The introduction of the Dandy way of life? My dear Palmieri, while such intent may seem laudable to one so young and full of idealism, your words set this middle-aged dandy’s fop-dar a-beeping. I hope you and your friend’s “grand scheme” does not involve flouncing around the quad in poofy shirts and knee breeches proclaiming the equiprimordiality of Beauty with a peacock feather in one hand and a dime-store quizzing glass in the other in some vain attempt to civilize the unruly, suds-swilling frat rats of U. Penn. You’ll only make a ridiculous spectacle of yourself. And your followers will no doubt be the sort of pencil-necked misfits who work at the local comic-book store, and there’s nothing dandyish about that.

But I react too rashly. Let us take a step back and look first to first principles. Before we can discover how to bring dandyism with us wherever we go, we have to ask first what dandyism is. But even before we do that, let’s discuss what dandyism is not.

Dandyism is not, as has often been claimed, a response to bourgeois, middle class or “mainstream” values, manners or fashions. There is nothing so bourgeois as affecting to despise the bourgeois. Nor is it a reaction to democratic leveling, perceived authoritarian rule, bureaucracy, technology or MTV. It is not a world-altering aesthetic movement that needs to be evangelized among the heathen, the vulgar and the unwashed. It has nothing whatever to do with alienation, angst, transgression, resistance or teenage rebellion.

Nor is dandyism a canvas upon which to paint a portrait of one’s pomposity; it is not some sort of sartorial telegraph for communicating one’s alleged spiritual superiority, supposed aesthetic authority, assumed poetic sensitivity, professed exquisite taste, or fictitious aristocratic lineage. Snobbery can be fun in its place, but it is hardly a credo. Dandyism won’t necessarily make you better that the useful persons around you, like your butcher, your baker, or your mechanic, but it may make you better in some ways than you were before. But then it may also leave you, as the histories suggest, penniless and drooling in a French insane asylum, penniless and on the brink of suicide, or penniless and cursing the wallpaper from your death bed in a cheap right bank hotel.

So what is it then? Simply put, dandyism is the study and practice of personal elegance.

At first blush that may sound a trifle shallow. But the closer you look, the more complexity you will see. And you will also see just how difficult the end is to achieve in real life. Edward Bulwer-Lytton (he of “It was a dark and stormy night” fame), is often remembered as one of the windiest novelists ever to disgrace the English language. Though Bulwer could indeed be a bloviating writer, he was nevertheless a great dandy. And he said it best when he wrote, “He who esteems trifles for themselves, is a trifler. He who esteems them for the conclusions to be drawn from them, or the advantage to which they can be put, is a philosopher.”

It is said that the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in one corner of the globe can cause a hurricane in another. As an aspiring dandy, you will set your mind toward observing and uncovering the meanings hidden in the seemingly insignificant trifles that others may miss: the fall of a coat, the tint of a woman’s hair, the tilt of a hat, the stress of a vowel, the grace of a gesture, the power of a word. The pinnacle of human trifling is, of course, fashion. As an aspiring dandy, you will become a student of fashion and its long and vital story amid human endeavor. Not just fashion in clothes, mind you, though you will watch this closely, but fashion in literature, fashion in advertising, fashion in music, fashion in morals, fashion in entertainment, fashion in art, fashion in thought and even fashion in politics. All of human folly and foible will be to you layered like a great ball of string, wound up with mystery and meaning. And as you unravel the ball the significance of the individual strings will grow more evident, just as their mysteries will deepen.

The exposition of trifles has itself become fashionable in literary circles in recent years, as some historians, grown weary of treating the same weighty events over and over, have taken to exploring the extraordinary influence of apparently incidental things like pepper, coffee, sugar, codfish and even the color mauve. It is a development that has substantiated what the dandy has known since Brummell: that the world is not only made up of trifles but it is governed by triflers, and that to apprehend society one must first comprehend folly. Always remember, as Bulwer also said, “Nothing is superficial to a deep observer.”

But we will speak more about fashion later on.

Whether you plan to write poems about trifles, paint canvases about folly, pen social critiques, or merely hang back and observe Vanity Fair’s foibles with a satirical glint in your eye and a quip on the tip of your tongue is up to you. The choice is also utterly irrelevant to your aspirations to dandyism. Contrary to popular belief, to be successful, a dandy needn’t be anything other than a dandy.

In the 19th century, dandyism became associated with the cult of art and beauty called aestheticism. This was due in no small part to the influence of men like Theophile Gautier, Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, Robert de Montequiou and others, who straddled the worlds of beau monde and bohemia, celebrity and notoriety, literary salon and opium den, whorehouse and painter’s studio. In the minds of today’s scholars and intellectuals, the two phenomena have become indelibly linked.

To add to the confusion, the aesthete was widely caricatured by popular magazines like Punch and in stage plays like Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta “Patience”. This snatch from the operetta’s key song, “The Aesthete,” is a parody of the young Oscar Wilde:

… Though the Philistines may jostle,

You will rank as an apostle

In the high aesthetic band

If you walk down Piccadilly with a poppy or a lily

In your mediaeval hand…

It is this cliché of the wilting, flower-waving aesthete in velvet britches and floppy hat, who faints at the sight of a Moreau and gushes paroxysms of joy over a Rossetti, that the contemporary world most associates with the dandy, particularly in the United States.

And the cliché lives on. No doubt you will meet the modern retro-eccentric version of the fin-de-siecle aesthete during your university sojourn. He will be resplendent in his neo-Victorian “Bunthorne” uniform, reminiscent of the costume Albert Finney wore in the film “A Man of No Importance.” You will see him in certain nightclubs and at certain parties, usually hanging around with the black-lipstick-and-eyeliner crowd, complaining in antiquated language about flip-flop-wearers, shabby grammar, reality TV, the Internet (except his own blog), athletes and how he was born into the wrong era.

The more contemporary — and to my mind the more authentic — aesthete often wears a uniform, too, but one that reflects the anger and revolt endemic to today’s art. Instead of waxing eloquent about a Whistler, our aesthete will proclaim the transgressive glories of Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” or Damian Hirst’s “Prodigal Son (Divided).” Oversized boots, paint-spattered jeans, an unruly mop and a crappy attitude are the likely accoutrements of his attire. Both of these are costumes, of course, and neither has much to do with elegance (although the retro-eccentric will often confuse his effeminate extravagance for it). Dandies don’t wear costumes, but carefully chosen attire.

You’re probably asking yourself, “But can’t a contemporary dandy be a contemporary aesthete?” And the answer is: “Absolutely.” But in the dandy alphabet, the “D” always comes before the “A.”

The fact is that there have been many dandies quietly dressing away for the last two centuries who could not care less about art for its own sake any more than they care about quantum physics. You rarely hear about them because they are only seen in passing, for they have few pretensions outside their craft. A few have been found dressing up the columns of certain publications. The New Yorker’s Robert Benchley and Vanity Fair’s Dominick Dunne are two of the ink-tinctured men-about-town that spring to mind. Others can be found in the more creative enterprises like marketing, such as Thomas Mastronardi, the branding expert recently pictured on Dandyism.net’s homepage. Still thousands of others dress each morning in splendid obscurity, doing so for no other purpose than to please themselves and the people they enjoy calling on. They may come from any of the more civilized professions, or from no profession at all. This is dandyism in its purest, most Brummellian form.

About now you’re probably thinking, “Well all of this is fine in theory, but what shall I wear?”

But the hour grows late, my dear Palmieri, my fingers are weary and I’m out of claret. You will have to wait until next time, when we discuss the dandy in practice.

* * *

My Dear Palmieri:

I am so glad to hear that your classmates and teachers consider you well dressed. It means that you have realized the first step in your dandiacal aspirations. If a dandy can be said to have any responsibilities, the first is to always be well dressed. The second is to be daring within the fluid limits of accepted taste. We will get to that in a moment. When last I wrote, we discussed the dandy in theory: what dandyism is and is not, the difference between the dandy and the various forms of aesthete and so forth. We determined that dandyism is, in short, the study and practice of personal elegance. Today we will explore dandyism in practice.

We left off last time with the question “What shall I wear?” To that I can only answer, “Why, anything you like, provided it is within the bounds of good taste, is appropriate to the occasion, and falls, as Max Beerbohm wrote, ‘within the wide limits of fashion.'”

Many have trouble with the “F” word, confusing overall fashionableness with vulgar trendiness. It should be remembered that, during his heyday as a theater critic and essayist in London, Beerbohm wore the elegant top hat and frock coat that were the man-about-town fashions of the Edwardian era. But half a century later, during his semiretirement in Italy, his visitors found him attired, albeit impeccably, in a simple suit, or casually in an ascot and cardigan — the everyday fashions of Europe in the 1950s. “The dandy,” he once wrote, is “the ‘child of his age,’ and his best work must accord with the age’s natural influence.” And bear in mind what Edward Bulwer-Lytton once wrote, “Never in your dress altogether desert that taste which is general. The world considers eccentricity in great things, genius; in small things, folly.”

It is a common misconception that one must wear a suit and tie every day, or even a sports jacket and tie, to be considered a dandy. In fact, one of the contemporary dandy’s greatest challenges lies in making casual dress fresh and daring. A fine pair of cords, a warm alpine sweater, silk scarf and a wool cap worn at a rakish angle are as dandyish as a bespoke suit if worn in, say, an Aspen ski chalet. In class, a burgundy velvet blazer and fitted black turtleneck can look as smart today as they did half a century ago. Look to your university’s rich heritage for insight into casual campus attire. Somewhere among UPenn’s moldering piles of stone you will find a long hall chock full with class portraits, sporting photos, trophies and other memorabilia. Observe carefully the styles of your venerable alumni and snatch from them the classics that will work for you today and give you panache tomorrow. And always remember that what you wear is less important than the style with which you wear it, for this is what separates the true dandy from the mere dandyologist.

There are many shops, department and warehouse stores that offer perfectly decent, classic apparel at affordable prices that you will be able to make work for you if you are patient, methodical, informed and inspired. Be sure to keep an eye on the so-called outlet shops, such as Polo and Brooks Brothers. There is also second hand and vintage. There’s no shame in buying second hand, if what you find works for you better than a new item would. I have found some of my best hats, for example, in antique shops. While some vintage shops are worth looking into for hard-to-find accessories and the occasional jacket or vest, steer clear of buying whole ensembles from days past.There’s nothing dandyish about looking like a gangster from a Jimmy Cagney movie. While we sometimes take our inspiration from history, we never copy it. A better bet is high-end consignment shops that serve tony charities like the ballet, the opera and the local upper-crust hospital. Rich people not only tend to have nicer clothes, but they cast them off more frequently than ordinary folk. And there is always, of course, eBay.

Before we step out to the shops it’s important to do some preparation. We can’t build a basilica merely by piling one stone on top of another. We need a solid foundation. It doesn’t matter if you are small, tall, slender or stout. You are an aspiring dandy, not an aspiring runway model, after all. But it’s vital to have a sound architecture upon which to build. To quote Beerbohm once again, “True dandyism is the result of an artistic temperament working upon a fine body.” There are many activities that can be useful in helping one build a solid framework. Fencing, dance, tennis, badminton and squash are excellent pastimes that can build strength, promote good posture and bring the bloom of good health into your pallid cheeks without putting you in a cast or depleting the stock of cash you should be spending on clothes.

I meant books, of course.

The temptations and pressures of a modern American university are myriad. Chief and most dangerous are the twin desires to both fit in and yet to stand out. You will face enormous pressure to play a part in a clique. At the same time you will feel compelled to make your mark. The easiest and most seductive of path is ill-conceived outrageousness. Instead of wearing peacock feathers and black lipstick, or strutting around campus with a boa constrictor around your neck, or reading “Howl” through a bullhorn from the top floor of the library, set yourself apart by the simple elegance of your dress, the confidence of your carriage and the unaffected grace of your deportment. At the same time, cultivate a wide acquaintance with your studied wit, your easy courtesy, and, moreover, your readiness to laugh.

Frequent interaction among a highly diverse acquaintance can be a great source of pleasure. It is also to be encouraged as means of instilling in oneself a sense of the foibles that move human behavior, which, as we noted in our last correspondence, is an essential quality of dandyism. But as with fashion, there is a difference between moving in society and becoming servile to its folly.

Always remember: to be a dandy is to be in control of who you are. In the words of Ellen Moers, the author of the quintessential history “The Dandy,” “The dandy’s achievement is simply to be himself. In his terms, however, this phrase does not mean to relax, to sprawl, or… to unbutton; it means to tighten, to control, to attain perfection in all the accessories of life, to resist whatever may be suitable for the vulgar but improper for the dandy.”

Should someone note, in a negative way, your attention to detail with regard to your dress and deportment, don’t bother to be angry, for in anger you lose yourself. Naturally, some people will always resent the smart and the stylish. Never mind them; cultivate that antique calm which will allow you to observe things and respond to them carefully with a critical eye and a sense of detachment. Says Machiavelli, “The world belongs to the cool of head.” Lastly, Never be afraid to appear judgmental: If you perceive a thing to be trendy crap, say so – and as amusingly as you can.

Naturally I wouldn’t for a moment suggest that you should never make close friends, go to a hip-hop show, fall in love, hold forth in the campus coffee house, get tipsy at a party or dance at a nightclub with your chums until 3 o’clock in the morning. On the contrary, you need to experience all that life has to offer. But Beau Brummell, according to his early theorist, Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, always applied this rule of thumb: “In society, stop until you have made your impression, then leave.” In other words, Brummell would “look in,” as the expression went, at ball or a party or a card game just long enough so that the other guests might take note and remember him. During these short appearances he would use his ready wit and charm to make his impression. Indeed, had Brummell continued to follow this simple rule, his distinguished career would have lasted far longer, for it was staying too long, drinking too much and playing for stakes too high that proved to be his undoing.

To this maxim I can only add that the best way to know when you have made your impression — and thus when to leave — is at the moment when you are having the best time yourself. If you always depart on a high note, people will remember you warmly and always want more of you, just as you will enjoy the memory of your time with them.

I would be a liar, my dear Palmieri, if I told you that I have heeded all of the advice I have offered you. But had I the chance to do my university days over, I hope that I would. Dandyism is not for the weak of character: It requires too much self-mastery to be easy. (And the hardest part, my friend, lies in making it look easy.) But it is also filled with pleasures. Some are simple and sensual: the luxurious feel of a fine velvet jacket at holiday time, or the disciplined snap of linen trouser cuffs as they swing around your ankles during a springtime stroll. Others are emotional and cerebral, like the satisfaction of knowing you are impeccably turned out, and that in order to be so required measures of education, creativity, self-knowledge and control that few others aspire to possess.

In you, Palmieri, I have great confidence. — MICHAEL MATTIS

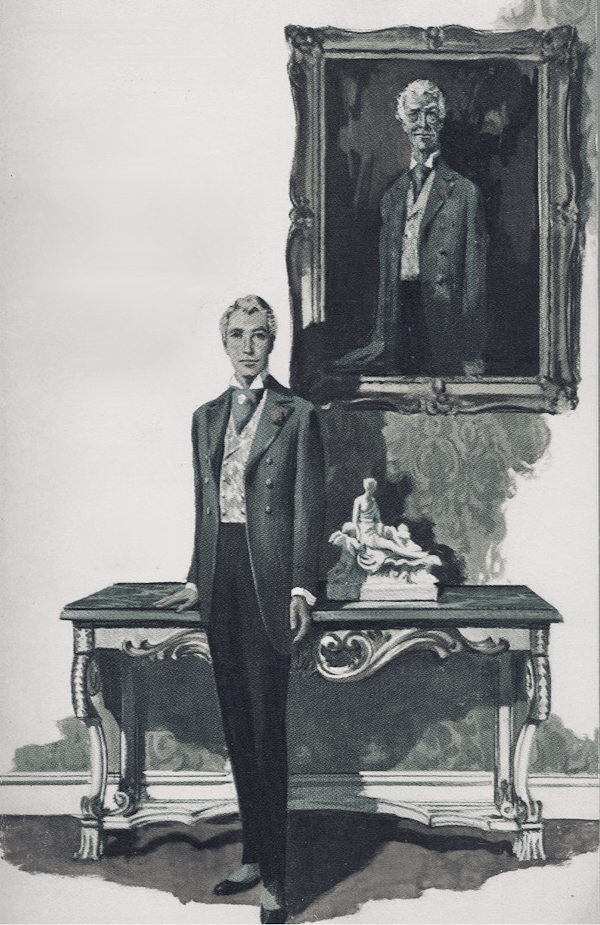

Image: Dorian Gray by Gregory Manchess, available from Lyra’s Books.