From “D’Orsay, or the Complete Dandy”

From “D’Orsay, or the Complete Dandy”

By W. Teignmouth Shore, 1911

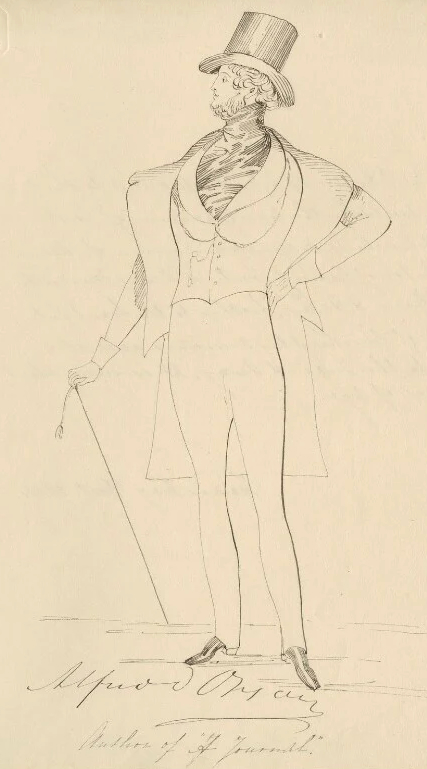

Image: detail of Count d’Orsay in the National Portrait Gallery

What a delightful fellow is your complete dandy. No mere clothes prop he, the coat does not make the dandy; no mere flaneur in fine garments; far more than that is our true dandy.

Though there is not any authority for making the statement, we do not think that we are wrong in asserting that on the day when Adam first complained to Eve that she had not cut his fig-leaf breeches according to the latest fashion dandyism was born. It is not dead yet, only moribund, palsied, shaking and decrepit with old age, blown upon by an over-practical world of money-spinners and money-spenders. Joy seems to have become a thing of which it is necessary to go in pursuit; in the golden days of the dandies it was a good comrade which came almost without hailing to those who desired its company. A real dandy would wither and wilt in a world where joy is so much of a stranger as it is now to most folk.

It is curious that there does not exist any history of the Rise, Decline and Fall of Dandyism, a subject fit for the pen of Gibbon. But the reason is, that to write it with anything approaching to accuracy and completeness, or with sufficient sympathy and insight, would stagger the painstaking pedantry of a German philosopher and tax the wit and wisdom of George Meredith. Perhaps some day the University of Oxford or of Cambridge, when it has finished trifling with ponderous records of kings and queens, of statesmen and soldiers, of men of science and of writers of books, will gather together a happy band of scholars and men of the world, and will issue to us a joint-stock history of Dandyism. Reform is in the University air; let us hope. Might not the Academic authorities go even further with profit to themselves and to the nation? Ought they not to found and well endow a Chair of Dandyism? Should there not be a Professor of Dandyism to teach the young idea how to distinguish between dress and mere clothes? Between those two there is as great a gulf fixed as between the gentle art of the gourmet and the mere feeding of the gourmand. To teach also the art of living and the history of dandies and of dandyism? In these prosaic days we are only too ready to learn how to obtain the means of living without acquiring also a knowledge of how to use those means to good purpose. The Universities should likewise institute scholarships of dandyism, to encourage the study of dandyism in our Public and Board Schools, in both of which it is so grossly neglected. These scholarships must not be of meagre twenties and thirties of pounds, but of several hundreds per annum, so as to enable the scholar to practise the arts that he studies. We commend this outlet for money to millionaires of a practical turn of mind. The future happiness of our race depends upon its dandyism.

The dandy has played a conspicuous part upon the stage of history: Alcibiades, Marc Antony, Buckingham, Claude Duval, Benjamin Disraeli prove the truth of this statement. It would be a nice point to decide how far their dandyism was part and parcel of their equipment for attaining greatness. At one period of English history the whole population of the country was divided between dandies and anti-dandies, Cavaliers and Puritans, the former dandified in dress, religion, methods of fighting and in morals. They were great dandies those martial Cavaliers, and so were a few of their successors, who flirted and frivoled at Whitehall under Charles II.

The literature of dandyism is varied, vast and interesting, but space forbids our doing more than briefly alluding to two of its lighter branches in English letters. The drama — or rather the comedy — of dandyism holds a very high place in the history of the British Stage. Lyly, the Euphuist, was a literary dandy of the first water, and his euphuism the height of dandyism in literary style. Shakespeare in Love’s Labour Lost has given us a whole comedy of dandyism, and in Mercutio a portrait of the complete Elizabethan dandy. But the comedy of dandyism was at its zenith in the days of Charles II. Congreve and Wycherley were its high priests, who preached through the mouths of their brilliant puppets the gospel of joy which the Court so ably practised. We have in The School for Scandal another bright flash of dandyism, though Charles Surface has too much heart for a true and perfect dandy.

In fiction we have many striking examples of dandiacal literature, notably Vivian Grey and Pelham, both written by dandies.

Dandies vary in kind as well as in degree, there being some who play at dandyism in the days of their youth, such for example as Disraeli; others who are pinchbeck dandies, falling into the slough of overdressing, such for example as Charles Dickens, who was a mere colourist in garments. There are the born dandies, Brummel, D’Orsay, George Bernard Shaw for examples, the last of whom was born at least 200 years behind his time; he would have been delightful at the Court of Charles the Merry. It is not necessary to be in the fashion to achieve the dignity of dandyism; GBS sets the fashion himself and is the only one who can follow it.

The psychology of the dandy has been much misunderstood, probably because it has been so little studied. What dandies have done has been told to us in many a biography, but what they have been — upon that point silence reigns almost supreme. Yet the mind of the complete dandy is well worth plumbing. Those who know him not will perchance advance the theory that a man possessed of a mind cannot be a dandy; as a matter of fact the reverse is the truth; he must possess mind, but not a heart.

Even so profound a philosopher and student of human nature — the two are seldom found in conjunction, which accounts for the inefficacy of most philosophy — as Professor Teufelsdroeck of Weissnichtwo has defined a dandy as “a Clothes-wearing Man, a Man whose trade, office and existence consists in the wearing of Clothes. Every faculty of his soul, spirit, purse and person is heroically consecrated to this one object, the wearing of clothes wisely and well: so that others dress to live, he lives to dress.”

Which proves that though undoubtedly German philosophers know most things in Heaven and on Earth they do not know all, though they themselves would never make this admission. Teufelsdroeck’s definition of a dandy is preposterously incomplete, showing that he did not possess insight into the heart and soul of dandyism. He perceived the clothes, but not the man.

The proper wearing of proper clothes is but part of the whole duty of a dandy-man. A complete dandy is dandified in all his modes of life; his sense of honour and his conceptions of morality are dandified; he is an epicure in all the arts of fine living, in all forms of fashionable and expensive amusement, in all luxurious accomplishments. He must be endowed with wit, or at least gifted with a tongue of sprightliness sufficient to pass muster as witty. He must be perfect in the amiable art of polite conversation and expert in the language of love. He must own “the courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s eye, tongue, sword”; he must be “the glass of fashion and the mould of form, the observed of all observers.”

A delightfully focused excerpt – I must obtain a copy… having already ordered a later D’Orsay biography by Willard Connelly (the most recent study by Mr Foulkes seems to have a few hundred rather dispensable pages).