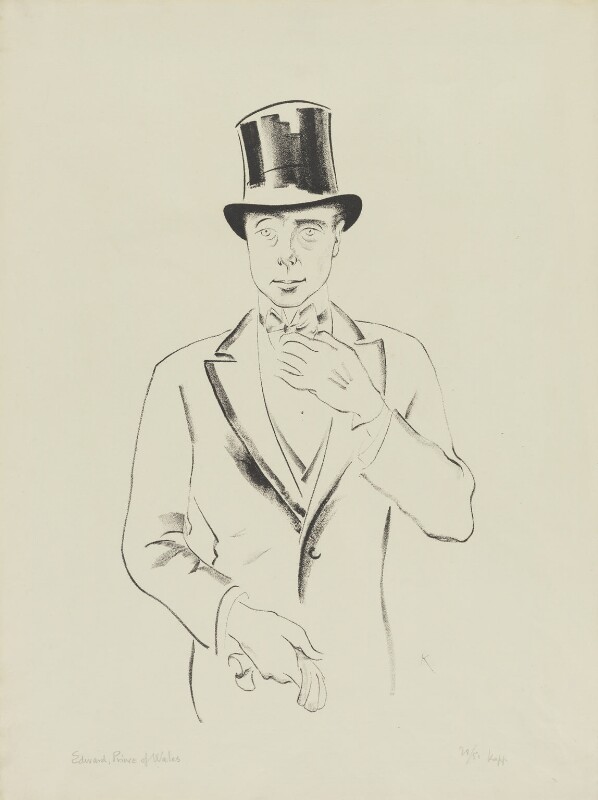

The Beau of Our Times

From Apparel Arts, Spring 1933

Article unsigned

“If there were no God,” said Voltaire some little time before he embraced Catholicism, “it would be necessary to invent Him.” Today the apparel industry echoes with religious fervor, “If there were no Prince of Wales, it would be necessary to invent him.” The National Association of Clothiers and Furnishers, during their meeting in Atlantic City in February of 1932, unanimously agreed that, of all the men in the world, England’s gallant Edward Albert alone deserved the title “Beau Brummel.” The one other male, it was naively recorded, who approached the Prince even remotely in the matter of influence was insouciant Mayor James Walker. And their report neglected to state whether the power exerted by this blithe individual should be praised as beneficial or condemned as corrupting and evil because of its jazzy sausage-causing lines and Broadway eccentricities.

It was the Prince who brought the derby — or, as the English would say, the bowler — back to popularity after the War. Appearing in a bowler, he brought the reign of the soft hat to a sudden and timely end: derby sales in Piccadilly doubled overnight. It was the Prince who, when he donned a brilliantly hued Fair Isle Sweater knitted for him in the Shetlands, led the weavers of that locale out of the darkness into international limelight. Though he wore the sensational sweater for only a single hour on the links at St. Andrews, Shetland weaving trade jumped over a million dollars a year. University undergraduates at Nebraska and Illinois subscribed, without a second thought, to monastic diets to corral funds enabling the purchase of these rather gaudy pullovers. It was the Prince who, at Le Touquet, golfed in black and white plus fours, bright blue shirt, and a salmon pink sleeveless jumper… sent outfitters scurrying madly. That very night an airplane, loaded with salmon pink jumpers, nosed out of London for Paris. It was the Princely predilection for pith helmets that caused Rio de Janeiro shops to move 5000 of them in short order during his Brazilian visit… a Princely sojourn in Buenos Aires that caused local clothiers to market more evening clothes in one week than ordinarily they sell in a year.

So rigorous in fact is this Walesian influence that it is fascinating to conjecture just how far his followers would go. Until Edward Albert vetoed the custom, it was considered de rigueur to wear gloves with formal evening dress. Once when the Heir Apparent rose with a cigarette between his lips, everyone thought the move signaled the introduction of a modern fashion. But it was merely an oversight: the Prince apologized, and males relinquished the prerogative of shrouding their dancing partners in tobacco some to Apache exponents. But when Prince walked down the gangplank on his return from South America sporting a boater, London haberdashers, caught completely off guard, sent frenzied wires to wondering suppliers demanding posthaste delivery of stiff straws. HRH initiated the combination of the white waistcoat, and though Alfonso, formerly King of Spain, is accredited with its creation, the double breasted dinner jacket worn over a soft shirt constituted no fashion actuality until Wales took it up. He made of every Parisian florist a devoted slave by wearing a boutonniere, a deep red carnation (a whimsy in keeping with gay night club peregrinations) to add a suitable fillip to informal evening dress.

When in 1924 all America favored the narrow brim hat turned up all the way round, Edward of Wales’ wide brim snapped down… shaded his royal eyes from the sun as he witnessed the International Polo matches at Meadowbrook. The American fashion pendulum reversed its direction the moment he took his place among the spectators: within a year narrow brims had become museum pieces. On the memorable visit in ’24 his repeated choice of a red and blue Guards stripe necktie worn always with a blue shirt sent this fashion quirk from his own solitary perch on its apex downwards through the stratas of the fashion pyramid to the broad base made up of the cut-price customers of Lennox Avenue.

HRH may be held responsible for the second to last revival of Glen Urquhart Plaid clothing. By favoring double breasted suits in chalk stripes over a blue flannel ground, he sent woolen designers into epoch-making conferences. The most important note in London Spring woolens is provided by flannels with chalk stripes, reddish Havana brown with white chalk stripes, grey flannels in many tones with pale blue chalk stripes. Edward Albert revolutionized the fur coat, transformed it from an unsightly amorphous thing into well-cut garment with as much swagger and smart good look as any form fitting cloth contemporary. He even set the style for the Boy Scouts by appearing, after the War, in shorts.

Today retailers can thank the Prince for the popularity of the hacking scarf, the backless dress waistcoat, the wide spread collar with its accompanying big knot necktie, the tab-collar shirt, and the polka dot foulard muffler. The fact that he is at present favoring a cap (of his own introduction) with one piece top sewn on to the brim in patterns of bold brown and white houndstooth check, and in his own Rothsey plaid, that he wears flannel shirts, cream colored ground with Tattersall pattern checks of yellow and black, blue and black, and brown and yellow, and that his fur trimmed coat flaunts a black Persian lamb collar carries as much weight with acute members of the apparel industry (from manufacturers to retailers) as do car loading figures to Stock Market Statisticians. It has become an automatic procedure for manufacturers to “put the Prince into their line.” It has become axiomatic for clothiers’ salesmen from the finest metropolitan shop down to the street hawker who vends his wares with a weather eye peeled for the cop on the corner — to use as a weighty closing argument: “The Prince of Wales is wearing it.” On every selling trip this royal traveling salesman has been dogged by newsreel photographers and reporters. His moments of privacy, out of eyeshot of the entire civilized world, are few and far between. Of consequence, as prime ambassador of the Empire, it is absolutely vital that he should appear at all times royal in manner, in attire.

Now good taste in selecting clothes is not an invariable adjunct to royal blood. King Edward, for all his reputation for bonhomerie, leaned toward bizarre in dress. London will never forget his trousers, creased at the sides. Today Queen Mary’s hats have given many a Paris couturier the migraine. And though David has exhibited his impatience with convention by appearing in a dinner jacket with a pullover sweater for a waistcoat, and is rumored to have donned (at view of the London Police in Hyde Park) with formal black coat and silk topper, a pair of rough tweed trousers with rolled cuffs, his natural interest in detail usually makes him the best turned out man in an assemblage. It may be true that he appeared at a luncheon given in his honor in Copenhagen on the occasion of the opening of the British Trade Convention in a cutaway coat with a soft collar, but as a rule his sense of responsibility throttles these youthful uprisings in the face of tradition. He may be interested in countless affairs from aviation to socialism, from re-forestation problems to welfare of England’s unemployed, but he still finds time to select his own clothes. And he has a fine flair for pattern, color and cut. In fact, while examining swatches, he may even say, “I like this, but I would like to see it with a yellow over plaid.” The tailor passes this information to the mills: “His Royal Highness likes this piece, but wishes to see it with a yellow over plaid.” The mill cooperates and the Prince has created a new design.

Only the most deserving firm receives the royal warrant. And though they receive the greatest part of his trade, shops other than those he has honored in this fashion, get some of his business. After a store has served him well for some years and has also earned an enviable record with the Prince’s acquaintances, it is granted the privilege of displaying the crown with the three plumes and the legend “Ich Dien” over the words “By Appointment to HRH The Prince of Wales.” Should the appointed, through some unforeseen catastrophe, fail, the management automatically loses the royal warrant.

The Prince’s wardrobe comprises what may be labeled without fear of refutation, the largest single collection of male attire in the modern world. There are the ceremonial robes, the accessories to the court dress, the ancient tartans of the Lord of the Isles which HRH wears in Scotland, his Guard’s dress, army and navy uniforms, the magnificent robes prerogative to the title Wales, Boy Scout uniforms, university robes, together with all the accoutrements incidental to formal day and evening, informal and sports wear. Unfortunately the inquisitive reporter cannot gain entrance into the wardrobe chambers of York House to make a detailed accounting of what would be found there. Nor are there extant press agent accounts of its treasures as there might be if Wales were a cinema star. None but the royal valets, who find year round employment caring or the princely habiliments, know just how many hats, and ties, just how many pairs of shoes, just how many overcoats and pairs of gaiters Edward Windsor owns.

British biographers grow a bit self-conscious when they discuss their Prince’s fame as the well dressed man. Somehow or another they seem to think this sort of distinction might be interpreted as a slur against his manliness. For example, “He follows his own tastes to a large extent, but a feature of his garments is their masculinity. Although the Prince requires the services of two valets, he personally superintends his own wardrobe and regularly inspects his clothes in order to see that they are well preserved and that his stock is not too extensive. He does not believe in purchasing clothes above his ordinary requirements. As a rule HRH has a horror of appearing different from other men, but in the matter of dress he can carry uncommon fashions (before they are imitated) with perfect ease and shows no embarrassment on those occasions when he happens to be dressed differently form his companions. On one occasion when he was attending a banquet with his father and brothers, the Prince of Wales was the only person present who wore a flower in his buttonhole. It would have been an easy matter for him to remove it without notice, but the Prince preferred to follow his own fancy and the blossom graced his lapel throughout the function.”

That the Prince possesses fifty suits is regarded by the biographer a canard — nevertheless, a recent press dispatch from London reveals that when HRH left the capital for a week’s sojourn in the country, his luggage included eight suitcases, two hat cases, and three trunks, all tightly packed. No one has ever accurately reported the impedimenta necessary to a major Walesian journey.

Any competent analysis of the royal wardrobe must take into consideration at the very outset the fact that this charming citizen of the world is ever playing a dual role. For in his official capacity as prime figure in all Court ceremonies, as the Prince of Wales at a garden party at Buckingham Palace, or as the Great Steward of Scotland at some age old function, he is himself dictated to by the potent forces of tradition and convention. On such occasions, as also in the matter of formal and afternoon wear (where the only variations possible affect the placing of the buttons on the jacket sleeve or binding of braid), his dress approximates that which other holders of the title have worn before him. Only when he becomes the diplomat at large and salesman extraordinary has he a genuine opportunity to dictate the fashions in men’s apparel. Even then his choice of clothing may be determined by affairs of state: he wears Irish tweeds in Belfast, Scotch woolens at St. Andrews.

Fashion reporters will tell you that, in reality, clothes to the Prince of Wales are a bore. That he dresses merely for the trade. And that the limelight really belongs to Prince George, and to the Duke of Westmoreland, who is responsible for the recent revivals of both the two-vented jacket and of the Glen Plaid. In contradicting these contentions, one refutes the reference to the Prince’s apathy by alluding to the fact that he still sees to it, at times, that one tailor makes his coat, a second, the trousers, and a third, the waistcoat, because HRH feels some experts make certain parts better than others… answers the charge of waning influence by quoting a recent Belfast report which states that on the latest Irish trip hats stores were completely cleaned out of toppers by citizens eager to meet their Prince suitably attired.