From Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1862

Article unsigned

MR. THACKERAY tells us that having, as he supposed, created his famous Captain Costigan out of innumerable odds and ends and scraps of character, he was one night, while smoking in a London tavern, surprised by the entrance of the very man himself, with the same little coat, battered hat, and twinkling eye with which he had been presented in the pages of Pendennis. When the novelist asked the newcomer if he might offer him a glass of brandy and water, the reply was, “Bedad, ye may; and I’ll sing ye a song” — given in the very brogue with which he had endowed his own tipsy old vagabond. “How had I come to know him? how to divine him?” asks Mr. Thackeray. “Nothing shall ever convince me that I have not seen that man in the world of spirits.”

If Captain Gronow, formerly of the Grenadier Guards, and M.P. for Stafford, had happened to call upon Mr. Thackeray, he must, in like manner, have been recognized as the “Major Pendennis” whom he thought he had created. And now that the great satirist has read the little book of the Captain, he must be convinced that he must have known him in the spirit long before the Major was created.

“Who is Captain Gronow?”

He is the last of the “Dandies” of the Regency of George IV.; the sole survivor—unless we except the present octogenarian Prime Minister — of the favored mortals who, forty years ago, danced at Almack’s with the fair and frail Lady Jersey; dined at White’s with Alvanley, Kangaroo Cook, Hughes Ball, Red-Herring Yarmouth, and other worthies who have long passed the Styx; who had looked with hopeless envy upon the wonderful coats and miraculous cravats of Beau Brummell and Gentleman George; who knew the men who had penetrated the sacred mysteries of Carlton House; and who never appeared by daylight until afternoon, when the world was sufficiently aired for their advent.

In 1812 Gronow, a lad fresh from Eton, received an ensign’s commission in the Guards, was sent to Spain, where he showed pluck and spirit; went back to London and was admitted to the most select circles of fashion, being one of the half dozen out of three hundred officers of the Guards who had vouchers for Almack’s, whose sacred portals were jealously watched by the lady patronesses; and which no mortal man might pass except in full dress. Wellington himself, coming in trousers, was once remorselessly turned back. Gronow now speaks somewhat irreverently of the seven lady patronesses, whose smiles or frowns forty years ago consigned men and women to happiness or despair. Lady Jersey’s bearing was that of a tragedy queen, while attempting the sublime she frequently became ridiculous, being inconceivably rude, and often ill-bred. Lady Sefton was kind and amiable; Madame de Lieven haughty and exclusive. Princess Esterhazy was a bon enfant — a “good creature;” Lady Castlereagh and Mrs. Burrell, now Lady Westmoreland, were de très grands dames—“mighty stuck-up ladies.” The most popular of all was Lady Cowper, now Lady Palmerston.

Gronow gives a curious picture, representing one of the first quadrilles ever attempted at Almack’s. The ladies wear short-waisted, tight-fitting dresses, which give the impression of a total absence of undergarments. The gentlemen wear knee-breeches, and pumps, with square-tailed coats. The Roman-nosed personage whose head is well thrown back, as if to prevent his eyes from being gouged out by his pointed shirt collar, is the Most Noble the Marquis of Worcester. The lady whose hand he holds is the fair and frail Lady Jersey, high-priestess of the shrine of fashion. The active youth who kicks up his heels like a young colt, while he gallantly bends over to kiss the hand of his partner, is Clanronald Macdonald, otherwise unknown to fame. The lady who wheels around on tip-toe is Lady Worcester.

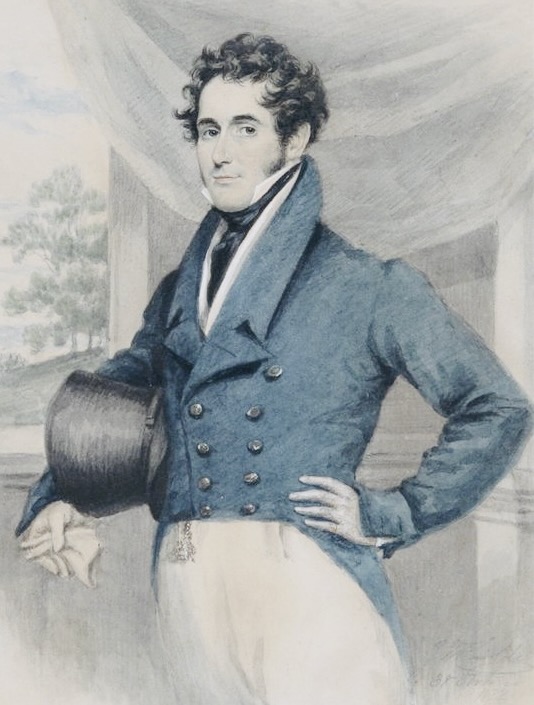

These delights were rudely interrupted. Napoleon broke loose from Elba, and the English cavalry were sent to encounter him. Young Gronow’s battalion was to stay at home; but General Picton, yielding to his importunity, consented to take him on his staff. A proper outfit was wanted, and the youth’s funds were at low ebb. He borrowed £200, with which he rushed to a gambling-house, and staking the money won £600 more. With this he fitted himself out in becoming style and set off. He had his share in the fight of Waterloo, accompanied the army to Paris, where he enlarged his knowledge of “life;” then went back to London to renew with fresh zeal his career as a dandy Guardsman. If not one of the great lights in the dandy firmament, he had yet a recognized place in it. His portrait in time appeared in the print-shop windows in company with those of Brummell, the Regent, Alvanley, Kangaroo Cook, and other worthies. It represents him, we should say in 1825; a dapper, be-frogged figure, with tightly-strapped trousers, silly face, and comical hat. And now, an old man of threescore and more, he sits down to give the world some account of his recollections of the great men and lovely women of his early days.

He writes in a dawdling, slip-shod style, worthy of Major Pendennis; but here and there manages to give an anecdote or sketch worthy of notice as a part of the picture of the times. To do the old Dandy justice, there is little of grossness in his anecdotes and reminiscences, though the men and women of whom he speaks were, with hardly an exception, as debauched and dissolute a crew as the world ever saw. Gluttony, drunkenness, gambling, and debauchery were the rule of their lives. Statesmen and judges went regularly drunk to bed; a “six-bottle-man” was looked up to with reverence; every man in “society” expected the gout, and made the pill-box his constant companion. Few of the names which appear in the history of the times are wanting in the scandalous chronicles of their day.

We have named gambling as one of the characteristics of the age. Young Gronow risked his borrowed £200 at the card-table. But this was nothing to the high play which prevailed at the clubs. Fox once played twenty-two hours in succession, losing £500 an hour. His losses in all amounted to £200,000. The Salon d’Etrangers in Paris offered to the English visitors abundant facilities for play. It was kept by the Marquis de Livry, who received his “guests” with a courtesy which made him famous throughout Europe. He was in looks the counterpart of the Prince Regent, who sent Lord Fife over to Paris on purpose to ascertain this important fact. His Lordship was a constant visitor to the salon, in company with a French danseuse, upon whom he spent £40,000 in a short time. Another visitor was Fox (not the celebrated Charles James), the Secretary of the British Embassy. He was never seen by daylight, except at the Embassy or in bed. At night he rushed to the salon, and if he had a Napoleon it was sure to be staked and lost. At last he was successful. He put down all he had, won eleven times in succession, broke the bank, and carried off 60,000 francs. Gronow calling upon him a few days after found his room filled with silks, shawls, bonnets, shoes, laces, and the like. “It is the only means I had,” Fox said, in explanation, “to prevent those rascals at the salon from winning back my money.” Lord Thanet was one of the most inveterate gamblers. He had an income of £50,000, all of which he dissipated at play. When the tables were closed for the night he would invite those who remained behind to stay and play in private. One night he lost £120,000, and when told that there had probably been cheating, simply replied, “Then I consider myself lucky in not having lost twice that sum.” A great gambler of the day was the Hungarian Count Hunyadi. He was for a time the rage, on account of his good looks, manners, and wealth. Ladies’ cloaks and cooks’ dishes were a la Huniade. For a while his luck seemed invincible; at one time his winnings were reckoned to amount to two million francs. He had two gens d’armes to wait upon him to his home, to guard against robbery. To all outward appearance he was the most impassive of players. He would sit apparently unmoved, his right hand in the breast of his coat while thousands were at stake on the turn of a card or a die. But his valet said that in the morning bloody marks were to be seen upon his chest, showing how he had pressed the nails into his flesh in the agony of an unsuccessful turn of fortune. Luck turned at last, and he lost not only his winnings but his fortune, and he was obliged to borrow £50 to carry him home to Hungary. Old Marshal Blucher was a constant frequenter of the salon. He generally managed to lose all the money he had about him, and all that his servant, who was wailing in the ante-chamber, carried. When he lost he would scowl fiercely at the croupier, and swear in German at every thing French. If he won the first coup he would allow it to remain on the table, but when reminded by the croupier that the bank was not responsible for more than 10,000 francs, he would roar like a lion, and swear in his own language like a trooper. The Bank of France was once called upon to furnish him with several thousand pounds, which, it was said, were to make up his losses at play. This, with other instances of extortion, led to the removal of the Marshal from Paris by the order of the King of Prussia.

Gronow mentions three or four successful gamblers. Among these were Lord Robert Spencer and General Fitzpatrick; being nearly “cleaned out,” they put their funds together and set up a faro bank in the club, with the consent of the members. The bank, as usual, was the winner, and Lord Robert soon found himself in possession of £100,000. He pocketed his gains, and never gambled again. Still more lucky was General Scott, the father-in-law of George Canning and the Duke of Portland. He was a famous whist-player, and was careful to avoid those indulgences which muddled the brains of his competitors, confining himself to chicken and toast-water; so he came to the whist-table with a clear head, and was able, according to the admiring Captain Gronow, “to win honestly the enormous sum of £200,000.” Brummell even found time, amidst the graver cares of the toilet, to do something in the way of gambling. One night he won £20,000 from George Harley Drummond. The loser was a member of the famous banking-house, and was requested by his partners to leave. They doubtless thought that the man who could take no better care of his own money was an unsafe custodian of that of others.

Brummell appears to better advantage in his brother dandy’s reminiscences than elsewhere. At Eton he was, according to Gronow, the best scholar, the best boatman, the best cricketer, and the “best fellow” in general. The fame of his accomplishments reached the ears of the Duchess of Devonshire and her set, through whom it became known to the Prince Regent, who sent for him, and gave him a commission in his own regiment, the 10th Hussars. But, unluckily, soon after joining his regiment he was flung from his horse at a review, and had his fine Roman nose broken. This foretaste of the perils of war was sufficient, and Brummell betook himself to the more congenial vocation of “leader of fashion.” He found a tailor capable of executing his sublime conceptions. We need not repeat the oft-told stories of the perfection of his coats, the grandeur of his cravats, the immaculateness of his linen, and the brilliancy of his boots. But it is given to no one man to excel in all things. There was a little dried-up old dandy, Colonel Kelley, whose boots excelled in polish those of Brummell himself, and the secret of the blacking was known only to himself and his faithful valet. One night a fire broke out in Kelley’s lodgings, and the poor old fellow was burned to death in endeavoring to save his favorite boots. All the dandies were eager to secure the services the valet who had the secret of the famous blacking. Brummell was first in the field. “How much wages do you require?” he asked. “My late master paid me £150; but I think my talents should bring more. I ask £200?” This was too much for Brummell. “Make it guineas, and I shall be happy to wait upon you,” he said. Lord Plymouth was the lucky man; he agreed to the £200, secured the valet, and with him the sovereignty of boots.

But Brummell’s taste was not evinced merely in coats and cravats. His house corresponded with his personal “get up.” His furniture was superb, his canes, snuff-boxes, and Sevres china exquisite, his carriage and horses superb; his library contained the best works of the best authors; and, in the words of Gronow, “the superior taste of a Brummell was discoverable in every thing that belonged to him.” He was famous in his day for his witticisms. With a single exception, those that have been recorded by Gronow and other admirers hardly justify his reputation. But that one, the famous “Who is your fat friend?” is sublime. As told by Gronow, it is even better than in the common version. The usual story is that Gentleman George, wishing to “cut” Brummell, who had taken the part of poor Mrs. Fitzherbert, encountered the Beau while walking in the street with Jack Lee. The Prince stopped and spoke with Lee, but took no notice of Brummell, who, as George turned to leave, drawled out the famous question. According to Gronow the scene occurred at a grand ball at Lady Cholmondeley’s, and the question was asked of Lady Worcester —the same whose hand we have seen so gallantly kissed by the active Clanronald Macdonald —to whom the Prince had just been trying to make himself especially agreeable. If so given, the thrust was a double one wounding the poor Regent not only as a dandy but as a ladies’ man.

The venerable Gronow also professes to set the world right as to another famous anecdote respecting the Beau and the Prince. According to him, Brummell had been excluded from the paradise of Carlton House on account of his espousal of the cause of Mrs. Fitzherbert. But after his famous coup of winning the £20,000 from poor Drummond he was once more invited. Things went smoothly at first; but by-and-by the Beau, elated at finding himself in his old society, took more wine than he could carry; whereupon the Regent, who was on the watch to pay off old scores, turned to the Duke of York with the words, “I think we had better order Mr. Brummell’s carriage before he gets drunk.” So he rang the bell; the carriage was called, and the doors of the Carlton paradise were closed upon the Beau. “This circumstance,” says Gronow, “originated the story about the Beau having told the Prince to ring the bell. I received the details from the late General Sir Arthur Upton, who was present at the dinner.” He indeed places this occurrence after the “fat friend” affair. But his memory of dates is hardly reliable. Brummell must have felt that this blow was one that could never be forgotten or forgiven by the Prince, and would not, we are sure, have been lured back afterward. We believe that it was the Beau’s revenge for having been turned out of the dining-room.

After this fashion does the Last of the Dandies gossip in his feeble way of the great men whom he had known in his younger days. We will select and abridge a few more of his reminiscences, of little account in themselves, but not without interest as giving glimpses of the times.

Among the officers and “men about town” was Colonel Mackinnon, famous for his strength and agility. He would creep over chairs, and scramble over balconies and housetops like another Gabriel Ravel. He would have made a fortune as a circus clown. Grimaldi himself acknowledged that the Colonel’s natural gifts in this line exceeded his own. “He was,” says Gronow, “famous for practical jokes; which were, however, always played in a gentlemanly way.” Thus: In a Spanish town he once undertook to personate the Duke of York. The authorities, in order to do honor to the Commander-in-chief of the armies of their ally, got up a grand banquet, terminating in the appearance of a huge bowl of punch; whereupon the noble Colonel plunged his head into the china bowl and flung his heels into the air, to the wonder and indignation of the grave Dons, who made a formal complaint to Lord Wellington. At another time Wellington, making a formal visit to a nunnery near Lisbon, was surprised to see Mackinnon among the nuns, dressed in the sacred costume, with his face smoothly shaved. This “gentlemanly joke” very nearly brought the Colonel to a court-martial.

Another worthy, whom Gronow calls “one of my most intimate friends,” was Captain Hesse, of the Guards, “generally believed to be a son of the Duke of York, by a German lady of high rank.” At all events, he lived when a youth with the Duke and Duchess, and was gazetted a cornet in his eighteenth year. He went to Spain with his regiment, was wounded, and received from a “royal lady,” a present of a watch, with her portrait, which was delivered by Wellington in person. On his return the Prince Regent sent Admiral Keith to demand the delivery of the watch and letters. Hesse gave them up, and was assured that the Heir of the Throne would never forget so great a mark of confidence, and would ever be his friend. But, adds Gronow, “I regret to say, from personal knowledge, that upon this occasion the Prince behaved most ungratefully; for, having obtained all he wanted, he positively refused to receive Hesse at Carlton House.” Hesse went to Naples, became involved in an intrigue with the Queen, and was expelled from the country. After fighting several duels, he was killed by Count L., an illegitimate son of the first Napoleon. “He died as he had lived,” says Gronow, “beloved by his friends, and leaving behind him little but his name and the kind thoughts of those who survived him.”

Lady Blessington, who knew this adventurer well while at Naples, gives a very different account of him. She says he was the son of a Prussian banker, who was ruined in the wars; he was patronized by the Margravine of Anspach, the divorced wife of an English nobleman, who sent him to England, commending him to the kindness of the Duchess of York, who got him a commission. He soon distinguished himself as a dandy, and gave out that he was a son of the Margrave and Margravine, born before marriage. The Princess Charlotte was captivated by his dashing manner. She smiled, then bowed, then wrote to him—and, finally, sent him her portrait. Vain of his conquest, Hesse could not keep the secret, and it became public talk. The Princess was scolded and Hesse sent off to Spain, in hope that he might get killed; but he kept portrait and letters, and was with difficulty induced to give them up, through the instrumentality of Keppel Craven, a son of the Margravine by her old English husband.

After Brummell’s deposition Lord Alvanley became King of the Dandies, and all the “good things” said at the clubs were attributed to him. Gronow ransacks his memory for some of them, but they are not worth reproducing. But dandies, like other mortals, grow old and bloated. The great George himself was not exempt from the common lot’s disguise it as he might for a while by tight lacing and trousers, into which he could only get by the aid of two stout valets. How could the lesser worthies hope to escape?

Gronow gives portraits taken in 1830, or thereabouts, of those who were the resplendent dandies of 1815. Alvanley looks like a pig in broadcloth. Red-Herring Yarmouth, the Alcibiades of his day, has become a stout gentleman with cane and heavy Petersham coat. Kangaroo Cook and Hughes Ball, spite of tailors and boot-makers, show traces of old port and blue-pills. Lord Fife looks stupid enough to have wasted a fortune on a ballet-dancer. Prince Esterhazy, of the famous coat, worth half a million, from which pearls worth a thousand dollars were lost every time he wore it, has grown to look like a thrifty merchant; and Lord Londonderry, whom Walter Scott, ten years before, immortalized as the one who bore himself most nobly in the coronation, presents the perfect picture of our “fat friend,” the once dandy Regent. All these have, we trust, gone down to Orcus, and their works have followed them, Gronow being alone left to tell. “Si monumentum quoris, fimetum adspice.”

Gronow was one of the first English officers who entered Paris. He rushed at once to the Cafe Anglais, where he ordered a beefsteak and pommes de terre in addition to the customary potage and fish. The wines he thought were sour; but as the dinner cost only two francs he was content, as he should have been, seeing that in London one could not get a genuine French dinner under three or four pounds, a bottle of claret or Champagne costing a guinea. The Paris of 1815 bore little resemblance to the city of our day. The Champs Elysees had but few houses; the roads were ankle-deep in mud, and only lighted by a few lamps suspended from cords which crossed the streets. Here the Scotch regiments were bivouacked, the Parisian women thinking the bareness of their lower limbs highly indelicate. The ladies wore short, scanty skirts, with no waists to speak of, while their bonnets projected a foot beyond their faces. The men wore blue or black coats, baggily made, reaching to their ankles, with enormous bell-crowned hats. The British beauties, who soon began to flock over, wore long, strait pelisses, the body of one color and the waist of another, with little bee-hive bonnets. The dress of the English gentlemen was a brown or light-blue coat, reaching nearly to the heels, with brass buttons; short pantaloons, big waistcoat, and an enormous muslin cravat, hiding the lower part of his face.

The Allies in Paris had a difficult part to play. The English were kept well in hand by Wellington; but the Prussians, who remembered the outrages of the French when they occupied Berlin, were ferocious. Old Blucher wanted to sack Paris, and especially to blow up the bridge of Jena, and was hardly restrained by the Iron Duke. The Cafe Foy was the principal rendezvous of the Prussian officers, and here came the French half-pay officers purposely to pick quarrels. A general melange often ensued: in one of these fourteen Prussians and ten Frenchmen were killed or wounded. Duels between Frenchmen and foreigners were an everyday occurrence. Gronow relates a score of instances which would well grave a history of dueling. One of his friends, dining at a cafe, observing a Frenchman rudely staring at him, started up and beat him over the head with a long loaf bread. A duel followed, in which the Frenchman was shot. One of his relatives challenged the Englishman and was also killed. A French colonel, a notorious duelist, walked out into the street, saying he was going to bully an Englishman. He encountered, unluckily, a friend of Gronow; a quarrel ensued, the Frenchman was knocked down; cards were exchanged. The Frenchman came on the ground boasting how many men he had killed, adding, “I’ll now complete my list by killing an Englishman.” The bully was shot dead at the first fire. His second challenged the Englishman and got a shot in the knee, which lamed him for life. The Englishman received forthwith eleven challenges from as many French officers; but the Minister of War interfered, threatening to place the officers under arrest. Quarrels were not wholly between Frenchmen and foreigners. There was bitter blood between Bonapartists and Bourbonists. Tallyrand and Fouche tried to have Napoleon arrested and shot as Rochefort, whither he had fled. To the honor of the Duke of Wellington, who had control of the Semaphore telegraphs of the time, he refused to allow them to transmit the order. He also tried in vain to prevent the judicial murder of Marshal Ney.

Our venerable dandy reproduces, in a feeble way, the London club gossip of his time: Mrs. Clarke, the mistress of the Duke of York, finding the allowance of her lover insufficient, set up a thriving business in the way of selling commissions in the army and preferments in the church. This came to light: the lady was summoned before the House. Her testimony, given with the coolest impudence, was damnatory of the Royal Duke, who resigned his office as commander-in-chief and broke off with the woman. She threatened to publish his letters. The Duke bought them at an enormous price, and secured for the lady a pension, provided she would leave England……On the day after the coronation of George IV., Coutts, the uxorious old banker, bought for £15,000 the magnificent diamond cross which the Duke of York had borrowed for that occasion from Hamlet, the Hebrew jeweler, and presented it to his young wife. She had commenced life as Harriet Mellon, the actress; became the mistress of Coutts, who married her after the death of his wife, and when he himself died left her the whole of his immense fortune. She then married the Duke of St. Albans, but kept her money at her own command; and upon her death left it to Miss Burdett, the grand-daughter of the old banker, upon condition that she should assume the name of Coutts. It amounted to two or three millions of pounds, and Miss Burdett Coutts, the richest heiress in England, had her choice of husbands. Among the aspirants was Prince Louis Napoleon, and it is Miss Coutts’s own fault that she is not now Empress of France……Hamlet made a good thing out of the young Earl of C.; he sold him at one time jewels for £30,000, and, as the Earl was not of age, gave him credit at a round rate. The jewels were given to a stage dancer of not doubtful character. The lady, says Gronow, is now living on her estate in France in the odor of respectability……The Prince Regent learning that the poor club-men had to pay high prices for bad dinners —nothing, in fact, but joints, beef-steaks, boiled fowl with oyster sauce, and the like — was moved with pity, and proposed that Wattiers, his own cook, should take a house and organize a dinner club. The club was established; the dinners were exquisite; Gronow became a member, and frequently saw the Duke of York appeasing his noble appetite. But the play was so high that few could stand the pace; and Wattiers’s ran down in a few years. One night Jack Bouverie, brother of Lady Heytesbury, was losing largely and grew irritable. Raikes, who not long ago published his reminiscences, laughed at him. Jack flung his play-bowl at the head of the joker. This made the “city dandy,” as Gronow sneeringly calls him, angry; but no serious results followed…..Sir Benjamin Bloomfield — who could play the violoncello so well that he was worthy of accompanying the Regent himself, and who had long been a favorite at Carlton House — had discovered that the Regent had given certain jewels which belonged to the Crown to a fair and frail marchioness. She had been compelled to send them back, but in revenge had Bloomfield exiled from Carlton House. He was created a peer and sent minister to Sweden……The Duke of Gloucester, who was thought to be as near a fool as a Royal Duke could be, and went by the name of “Silly Billy,” got off a good thing. When his brother, William IV, assented to Lord Grey’s proposition to make the Reform Bill pass any how, poor Gloucester cried out in triumph, “Who is Silly Billy now?” General Palmer, to whom the Home of Commons had voted £100,000 in consideration of his father having invented the post-office system, had laid out the money in a French vineyard, and meant to give the English genuine clarets. His wines were tried at Carlton House, but did not suit the hard drinkers there as well as the manufactured articles to which they had been accustomed. The Prince Regent advised Palmer to root up his vines, and try to produce something better. He complied, was ruined, and finally became a mendicant in the streets of London…….There was Long Wellesley Pole, who had owned Wanstead, one of the finest mansions in England. He had married an heiress with £50,000 a year, but had spent it all, and was now a beggar. Indeed, he would have starved had not his cousin, the present Duke of Wellington, allowed him a pension of £300 a year, upon which he managed to keep soul and body together……There was Lady Cork, who used to give parties to all the lions of the day. She would steal every thing upon which she could lay her hands, but would send back her spoils the next day, fearing to be prosecuted. People thought her ladyship not quite in her right mind……What a sad thing happened at Graham’s, one of the less aristocratic clubs. A nobleman’s Gronow, at the distance of thirty years, will not mention his name of the highest position and influence in society, was detected in cheating at cards, and after a trial which, as the Captain euphemistically phrases it, “did not terminate in his favor, died of a broken heart.” Madame Catalini, the great singer, was a good woman, a model wife and mother, but was very fond of money. She, with her husband, M. de Valabreque, had been invited by the Marquis of Buckingham to spend some time at Stowe, with a numerous and select party. After dinner she was always asked to favor the guests with a song, and complied with the most charming readiness. When the day of departure came Valabreque handed the Marquis a little billet. The husband of Catalini took good care for her. She had been insulted by a German baron. Valabreque challenged him. The weapons were sabres; the German had half his nose cut clean off……An odd accident happened to the half-cracked beau Romeo Coates, famous for his fur coat and diamond buttons and knee-buckles. He undertook to play Romeo as an amateur at the Bath theatre. Unfortunately, his crimson nether garments, which were of too tight fit, gave way, and from the rent protruded a quantity of white linen sufficient to make a Bourbon flag, which the unconscious amateur displayed to the best advantage as he crossed and recrossed the stage. The dying scene was irresistibly comic. The audience demanded its repetition; he rose, bowed, and went through the act of dying again. Another repetition was called for, and Romeo was about to comply, when Juliet rose from the tomb and put a stop to the farce.

Such are the reminiscences with which our poor old dandy favors the world. Now and then, indeed, he came in contact with men who had something in them besides dandyism. Thus in 1815, he met at dinner Sir Walter Scott, Byron, and Croker. Sir Walter ate like a Border-man, drank like the Holy Friar of Copmanhurst, and recited some old ballads. Byron was all show and affectation; said he did not like to see women at table, as he wished his faith in their ethereal nature to be undisturbed; but upon being pressed, owned that his dislike arose from the fact that they were helped first, and so got all the chicken wings, while he and the other hungry men were put off with the drumsticks and such like less delicate parts. He used to see Byron occasionally, especially at Brighton, where he used to go boating, jumping into the boat as briskly as though he was not lame. He was generally accompanied by a lad, who was thought to be a girl in boy’s clothes. Gronow knew little of Byron personally, but knew Scrope Davies, who told good stories of the noble bard, of which the Captain wishes he could remember more. One was of entering Byron’s sleeping-room one morning, and finding the poet with his hair in curl-papers. Byron was angry, but acknowledged that his lovely curls were produced in this way, adding that he was as vain of them as a girl of sixteen. He swore Scrope to secrecy — an oath which was kept as such oaths usually are. Scrope, who was for a time Byron’s most intimate friend, assured Gronow that the poet was very agreeable and clever, but vain, overbearing, and suspicious; he thought the whole world ought to be constantly employed in admiring him and his poetry.

Shelley had been a friend and associate of Gronow at Eton. There he was a thin, slight lad, with lustrous eyes, fine hair, and a very peculiar shrill voice and laugh. The paths in life of the dandy and the poet diverged widely, though they occasionally crossed each other. The last meeting was at Genoa, in 1822. Shelley sat on the sea-shore making his meal of bread and fruit. He was carelessly dressed; his long brown hair, already streaked with gray, though he was but twenty-nine, floated in large masses from under his broad straw-hat. He looked care-worn and ill. Recognizing his old schoolfellow he sprang up, exclaiming, “Here you see me at my old Eton habits; but instead of the green fields for a couch, I have the grand shores of the Mediterranean. It is very grand, and very romantic. I only wish I had some of the excellent brown bread and butter we used to get at Spiers’s. Gronow, do you remember the beautiful Martha, the Hebe of Spiers’s? She was the loveliest girl I ever saw, and I loved her to distraction.” They talked a little of old times. Shelley asked of old school-fellows, but would say little of his own plans and purposes. Byron’s name was mentioned. “He is living,” said Shelley, “at his villa, surrounded by his court of sycophants; but I shall shortly see him at Leghorn.” Dandy and Poet shook hands and parted. There was nothing in common save a few boyish recollections. Shelley was drowned not long after, and the world knows with what heathenish rites his body was burned by Byron and Trelawney. And now, after an interval of two-score years, his old school-fellow, the last of the dandies, writes down his few recollections of him beside those of Brummell, Alvanley, Kangaroo Cook, George the Magnificent, Colonel Hesse, and the other roués and exquisites of the day.

So the old dandy, the last of his tribe, gossips, in feeble way, of his times, promising, if the public lend him a patient car, to give them another volume of like character. We trust he will do so; for it is from such books, rather than from more pretentious ones, that true history is elaborated.