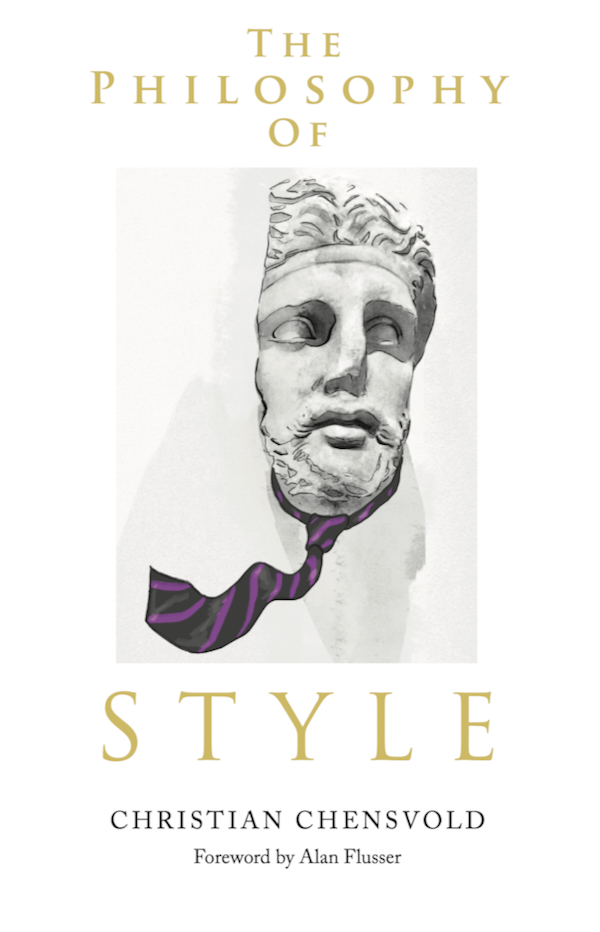

In 1988 I graduated high school and took off on my first solo road trip, and the adventure onto which I embarked was a quest for elegance. I ended up in Beverly Hills, as this Gomorrah of haute-bourgeois conspicuous consumption was the nearest facsimile reachable by motorcar. Within five years I was fluent in dandyism — particularly the Decadent variety — and all these years later have finally collected my thoughts on menswear and its various archetypes in “The Philosophy Of Style.” The book consists of essays, historical articles, divertissements, and three works of fiction set in the world of men’s style, including the title tale. Alan Flusser graciously provided the foreword. The chapter on dandyism contains three decades of musings on this fascinating and elusive topic, from my earliest published articles on the topic in 1994 to a section on dandyism as a spiritual path added right before going to press. Below is an excerpt. — CC

* * *

From “The Philosophy Of Style,” 2023

By Christian Chensvold

Archetypes earn their recognition. From the beatnik and starving artist to businessman and bureaucrat, all have claimed their position in the cultural vocabulary, branding their taglines and silhouettes on the American psyche.

But there is another type of masculine incarnation—sophisticated, imperious, and aloof—that is just as recognizable, though society struggles to name this cunning creature. And since that which can’t be named cannot be discussed, this misunderstood genius, this elegant outlaw, this rare incarnation of taste and wit, slips among the shadows of his time and place.

In this darkness of ignorance the dandy smirks, for he cherishes his obscurity. Were his secret to get out, aspiring dandies might start sprouting up everywhere. A sort of rebellious chameleon, the dandy at once defines his era and defies it, exemplifying his cultural milieu while simultaneously subverting it. Though dandies have always been and forever will be like comets, their appearance is rare but inevitable. A rebel with no cause but himself, the dandy is ideally a man of leisure; “free,” as one historian writes, “of all entanglements that interfere with taste.”

The father of dandyhood is Beau Brummell. One of history’s great nonconformists, Brummell was the son of a middle-class secretary who had no specific occupation, great fortune, nor claim to fame. But since what really matters is never what you know but whom you know, at Oxford Brummell befriended the Prince Regent George IV, who inveigled him into the loftiest levels of London society, where most men would have suffered altitude sickness. Famed for his truculent wit and blasé demeanor, Brummell’s style ran counter to the prevailing taste of the times, which was still suffering from baroque extravagance. By combining wit, which cuts, and elegance, which soothes, Brummell perfected the art of pleasing by displeasing. In doing so he created a horde of sycophants who copied his cool manners and faultless attire and attempted to distill the same magical elixir throughout London’s clubs and drawing rooms.

But no elixir was quite as potent as the celebrated Mr. Brummell’s. In a society liberated by affluence but chained by propriety, Beau Brummell filled the immensely important function of alleviating boredom, which he did through a supernatural recipe of mordant wit, a kind of polite impudence, and a simple and sober wardrobe. And so contrary to the word’s connotations for the past century, a dandy is not a wearer of ostentatious clothing. Brummell’s distinction lay in the subtle, almost subliminal, assertion of a style that was at once the repudiation of all other styles, even the ones he appropriated in his daring and modern creation. It was the cut and cloth of his suits, the shine on his boots, and above all the perfect knot of his cravat that men admired and sought to emulate.

Brummell’s French biographer—I would say hagiographer is the more appropriate term—was Jules Amadeus Barbey d’Aurevilly, an eccentric Romantic who certainly romanticized Brummell in his 1844 book “Of Dandyism and George Brummell.” The slender tome, a masterpiece of preciosity in style, gives birth to dandyism as a stance of the spirit, with Barbey insisting that Brummell’s “beauty was intellectual” and that his physical appearance bore all the marks of mind triumphing proudly over matter. Barbey’s analysis of the dandy soul, for a dandy is far from being merely a gilded shell, is written with a transcendental vocabulary. All the intangible aspects of the dandy, which diffuse like a fog and shroud him in mystery, are what interest Barbey and find their consecration in the metaphysical language he employs. Barbey concludes that the cold elegance, blasé mien, and calm exterior revealing strength all contribute to a resolute character basking in the refined tranquility of a kind of sartorial nirvana.

But in dandyism, a form of role-playing in which the dandy is simultaneously actor, director, and audience, there is often a stark difference between appearance and reality. Dandyism is often a mask concealing scowls and frowns. The spleen-addled poet Charles Baudelaire attempted to give dandyism a heroic quality, viewing it as a way of imposing order and beauty upon a chaotic and ugly world, which suggests that dandyism may be more relevant today than ever.

Congratulations on the publication of the book, Christian. I just ordered a copy on Amazon. I miss you at the helm of Ivy-Style.com, but I understand having to walk away from a project after such a long period. I hope all is well, and best wishes for your continued success.

I’m much enjoying these takes on dandyhood in an actual book…

(and underlining more than a few words – ‘Boulevardier’ being the best so far for my shillings!)

While your romance is for Belle Epoch sensibilities; mine have always been Futurist dystopian… forged by Logan’s Run and fermented by Ultravox.

You mention the geek’s wardrobe and introversion “does not make for a guy whose appearance makes a dashing impression” and plausibly so.

I was wondering if you’ve ever observed a ‘middle course’ … namely love of style but lack of inclination to become an exhibit simply for making an effort these days?

As a futurist dystopian, your moment has arrived. Now is your time to shine. Don’t hold back.

Well Logan’s Run is being re-booted this year – so yes, indeed! (just seems a shame to be on the wrong side of Sandman policy this time round ????)

(slight emoji miss-fire there)