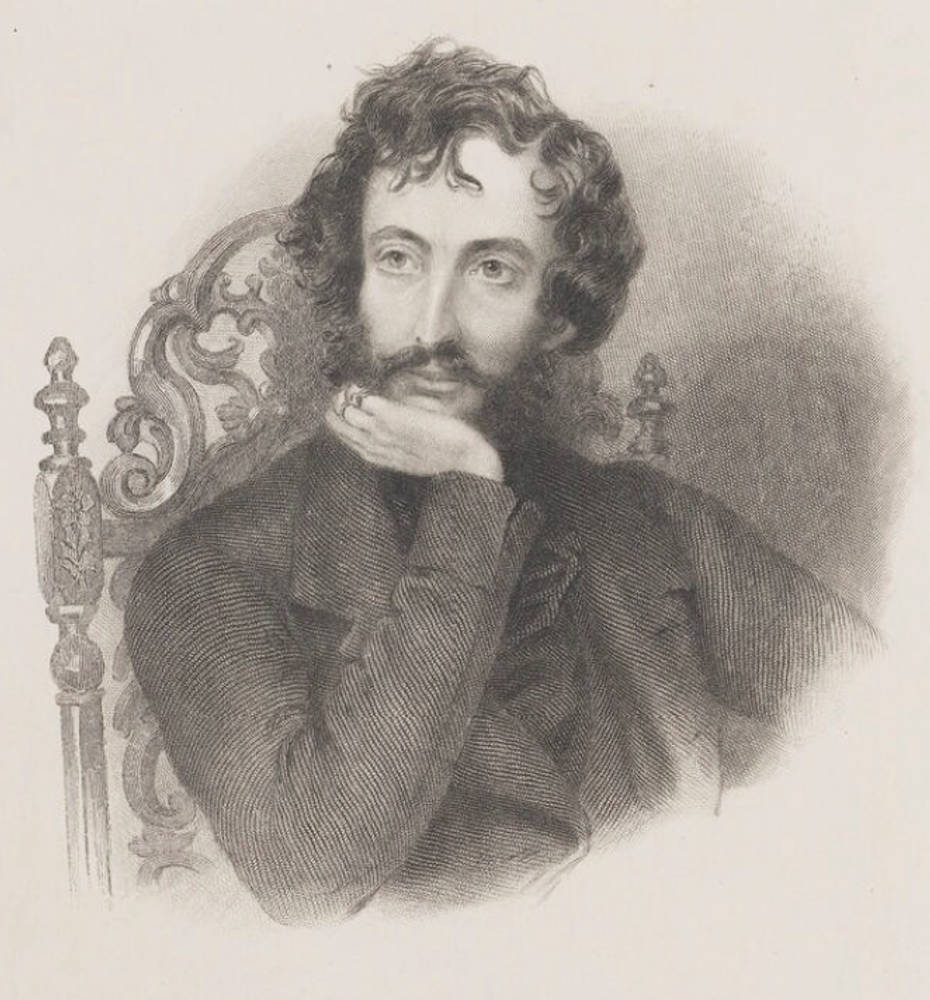

From “Pelham: Or the Adventures of a Gentleman”

By Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1828

1) Do not require your dress so much to fit, as to adorn you. Nature is not to be copied, but to be exalted by art. Apelles blamed Protogenes for being too natural.

2) Never in your dress altogether desert that taste which is general. The world considers eccentricity in great things, genius; in small things, folly.

3) Always remember that you dress to fascinate others, not yourself.

4) Keep your mind free from all violent affections at the hour of the toilet. A philosophical serenity is perfectly necessary to success. Helvetius says justly, that our errors arise from our passions.

5) Remember that none but those whose courage is unquestionable, can venture to be effeminate. It was only in the field that the Lacedemonians were accustomed to use perfumes and curl their hair.

6) Never let the finery of chains and rings seem your own choice; that which naturally belongs to women should appear only worn for their sake. We dignify foppery, when we invest it with a sentiment.

7) To win the affection of your mistress, appear negligent in your costume-to preserve it, assiduous: the first is a sign of the passion of love; the second, of its respect.

8) A man must be a profound calculator to be a consummate dresser. One must not dress the same, whether one goes to a minister or a mistress; an avaricious uncle, or an ostentatious cousin: there is no diplomacy more subtle than that of dress.

9) Is the great man whom you would conciliate a coxcomb? — go to him in a waistcoat like his own. “Imitation,” says the author of Lacon, “is the sincerest flattery.”

10) The handsome may be shewy in dress, the plain should study to be unexceptionable; just as in great men we look for something to admire — in ordinary men we ask for nothing to forgive.

11) There is a study of dress for the aged, as well as for the young. Inattention is no less indecorous in one than in the other; we may distinguish the taste appropriate to each, by the reflection that youth is made to be loved-age, to be respected.

12) A fool may dress gaudily, but a fool cannot dress well-for to dress well requires judgment; and Rochefaucault says with truth, “On est quelquefois un sot avec de l’esprit, mais on ne lest jamais avec du jugement.”

13) There may be more pathos in the fall of a collar, or the curl of a lock, than the shallow think for. Should we be so apt as we are now to compassionate the misfortunes, and to forgive the insincerity of Charles I, if his pictures had pourtrayed him in a bob wig and a pigtail? Vandyke was a greater sophist than Hume.

14) The most graceful principle of dress is neatness — the most vulgar is preciseness.

15) Dress contains the two codes of morality — private and public. Attention is the duty we owe to others-cleanliness that which we owe to ourselves.

16) Dress so that it may never be said of you “What a well dressed man!” — but, “What a gentlemanlike man!”

17) Avoid many colours; and seek, by some one prevalent and quiet tint, to sober down the others. Apelles used only four colours, and always subdued those which were more florid, by a darkening varnish.

18) Nothing is superficial to a deep observer! It is in trifles that the mind betrays itself. “In what part of that letter,” said a king to the wisest of living diplomatists, “did you discover irresolution?” — “In its ns and gs!” was the answer.

19) A very benevolent man will never shock the feelings of others, by an excess either of inattention or display; you may doubt, therefore, the philanthropy both of a sloven and a fop.

20) There is an indifference to please in a stocking down at heel — but there may be a malevolence in a diamond ring.

21) Inventions in dressing should resemble Addison’s definition of fine writing, and consists of “refinements which are natural, without being obvious.”

22) He who esteems trifles for themselves, is a trifler — he who esteems them for the conclusions to be drawn from them, or the advantage to which they can be put, is a philosopher.