Perhaps because of our Proustian and Balzacian education, we have been convinced for years that dandyism as we know it from literature and history has disappeared from the modern world. The more we study it, the more we believe that current pretensions to dandyism are egalitarian claims. No matter if it is based on historical misconceptions or ends a semantic tradition of Mignons, Petits-Maitres, Beaux, Lions, Macaronis, Incroyables, Muscadins, Bucks, Bloods and Dandies, the point is to persuade provincial readers of fashion magazines and conspicuous consumers that they can enter Brummell’s genealogy.

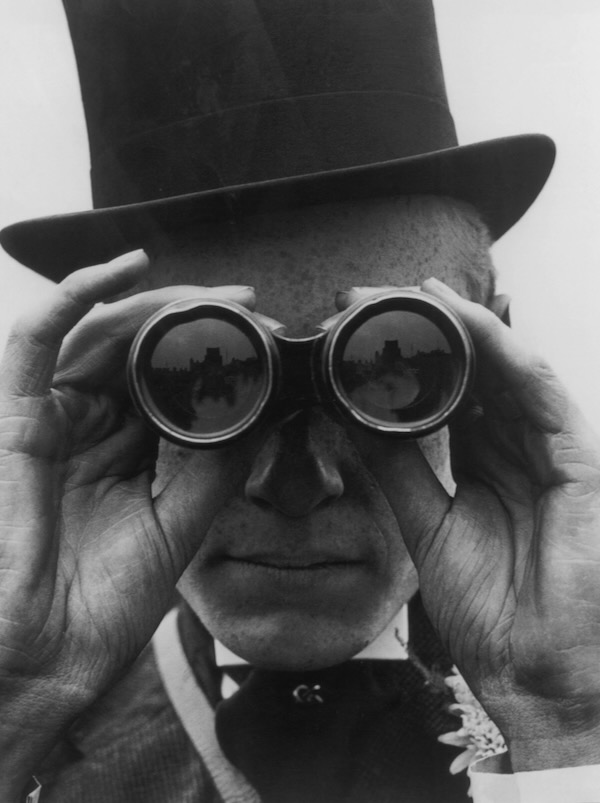

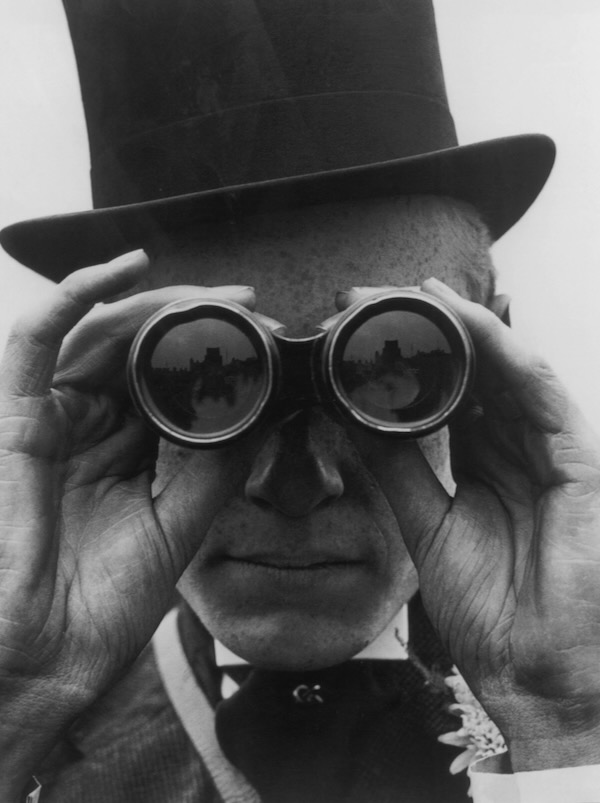

In spite of this, some modern gentlemen have applied aesthetic theories on clothes and manners. Inspired by Oscar Wilde or medieval courtesy manuals, their appearance and demeanor are snubs to the common people and signifiers to the happy few. Like their ambitious predecessors, they aim at founding a moral domination over society using elegance, wit and culture. Often they come from the collapsed aristocracy which has lost its riches (the former French royal family of Orleans, led by the Comte de Paris, has been out of money for decades), and its castles (except Charverny, which has been owned by the same family for centuries, most French castles are national monuments or the property of wealthy foreigners).

However, most of these gentlemen cannot personify their theories the way dandies used to. There are two reasons for this: First, real idleness has almost disappeared. After the Industrial Revolution, great families decided that the military (the Navy or Cavalry, of course), diplomacy or literature were not professions beneath them. Indeed, being a general, ambassador or academic had a certain prestige. Then scientific and financial careers entered the list because of their “elitism,” and because they paid enough to fund expensive leisure activities. Finally, today’s power is in industrial hands, and even lucky heirs, after a period of dissipation in Ibiza and Monte-Carlo (the two capitals of commonness), aspire to be on the cover of Forbes.

Second, independent thought has been increasingly banned. During the time of the great dandies, Alphonse Karr, Barbey d’Aurevilly and Jean Lorrain took refuge in journalism to express their cynical pronouncements in newspapers like Le Figaro, Punch and La Mode. Today’s journalists are not brilliant enough, and newspapers deal almost exclusively with facts, rarely with ideas. As a result, men of elegance must become normal workers and preserve their jobs. Can this be anything but a shame or act of cowardice? In finance, trade, science, diplomacy, journalism or the arts, even men of good breeding cannot be anything but an employee, and adopting Montesquiou’s tone and Barbey’s arrogance is a sure way to get fired.

The challenge for such men is to know how to live in this working world where intellectual debates are led by television producers, fashion journalists and sad moralists. Among friends there is no problem: Private parties are good places to strut and to forget your boss’ inadmissible insults. To mention Chaverny again, its owner would be just a pathetic museum keeper if he did not organize hunting and other traditional activities. Is it necessary to point out that tourists are not invited to his atavistic pleasures? The problem is working hours, when the theatres are closed. Dandyism is a total and exclusive philosophy, and therefore must be incompatible with a working life. What can be done?

Microbes are tiny organisms found everywhere. For people who cannot express their elegance and wit as they would like to, we suggest adopting this metaphoric microbian dandyism inspired by Yann Kerninon’s “Pour un dadaisme microbien.” It consists in a constant search for little dandyish behaviors in everyday life. It consists, for instance, in wearing almost invisible details (the “happy few” signs), in living as a dandy would live if he had to hide. We believe it is possible to have aesthetic debates on a coffee break, to have exquisite manners in the company cafeteria, to “play” with sad business attire, and to be brilliant, elegant and superior in a crowded subway as if it were Madame de Pompadour’s salon. Unfortunately, microbian dandyism leads only to microbian moral domination. Nevertheless, such a contamination could spread in people’s minds and manners.

The point in elegant life is not to copy Brummell, but to be a new Brummell. Never forget that dandyism was more than an aesthetic behavior: It was above all the expression of intellectual and social superiority. — FRANCOIS-XAVIER D’ARBONNEAU DE LA BACHELLERIE