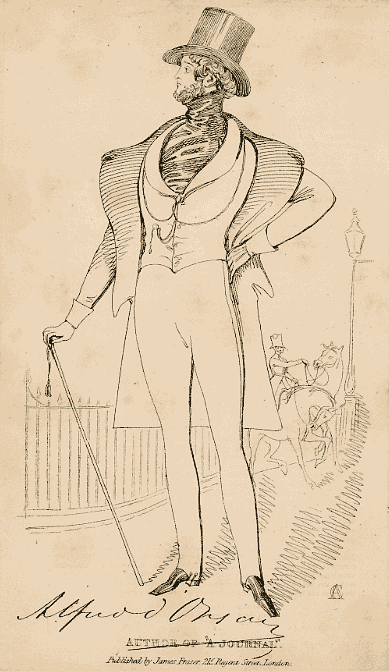

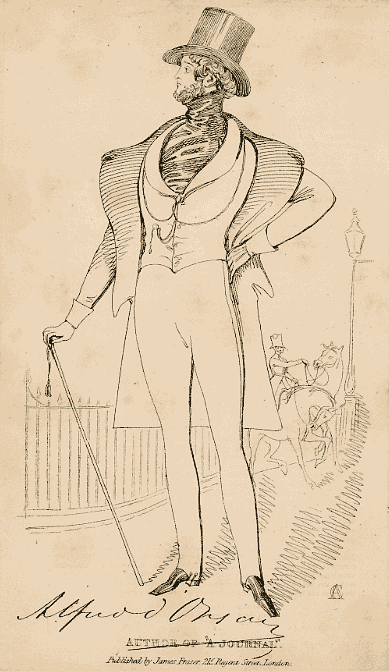

In 1844, at the height of his fame, Count Alfred d’Orsay found himself lampooned in print. Writing under the pen name A Man of Fashion, popular novelist John Mills published “D’Horsay: Or the Follies of the Day.” The whiff of scandal that ensued did little to obviate d’Orsay’s demand in society, perhaps because it failed to address the Count’s apparent seducing of wife, husband and daughter in the Blessington family. However, the book was immediately suppressed for its attacks on prominent men of the day, who are depicted engaging in various acts of questionable morality. “D’Horsay” is as tiresome and dated as one would expect, but we have excerpted a few descriptive passages for their historical value, as they show how the second-greatest dandy of all time was viewed in the diabolical monocle of a contemporary satirist. Some descriptions are of the character D’Horsay, while others are of his sycophantic imitators.

* * *

Excerpts from “D’Horsay, or the Follies of the Day”

By A Man of Fashion (John Mills), 1844

In the lower room of this house of counterfeit show, sat, or rather lounged, a leader of the votaries of pleasure. The Marquis D’Horsay was, indeed, “the glass of fashion, and the mold of form.”

From the color and tie of the kerchief which adorned his neck to the spurs ornamenting the heels of his patent boots, he was the original for countless copyists, particularly and collectively.

Even the brow which the ducal coronet occasionally pressed was proud to wear the hat imitated from the model, which every aspiring Tittlebat Titmouse of the age strove to copy in his gossamer. The hue and cut of his many faultless coats, the turn of his closely-fitting inexpressibles, the shade of his gloves, the knot of his scarf, were studied by the motley multitude with greater interest and avidity than objects more profitable and worthy of their regard, perchance, could possibly hope to obtain. Nor did the beard that flourished luxuriantly upon the delicate and nicely chiseled features of the Marquis escape the universal imitation.

Those who could not cultivate their scanty crops into the desirable arrangement had recourse to art and stratagem to supply the natural deficiency. Atkinson and Rowland revelled in the attempts. From the extreme east to the far west ends of London, lights and shadows of the Marquis were plentiful as daisies in merry May. Wristbands, both false and real, were turned over cuffs of every dye and texture, and, in short, from the most essential article of the modish lion’s dress to the most trifling, not an item was left confined to its pristine state of originality.

* * *

The Marquis D’Horsay’s figure, style, taste, manners, accomplishments, birth, extreme beauty of features, and dazzling station in the beau monde, made him, and well they might, the universally admired object with women, and scarcely less so of envy with men.

* * *

He was decked in clothes of many colours, cut in the very pink of fashion. A profusion of jewelry glittered in his ruffled bosom, on his fingers, and across his flaunting waistcoat. In his hand he carried a gold-mounted cane; and if all was not quite pure and real, it possessed the advantage of looking quite as well. His hat — for he did not uncover as he entered — was stuck very much on one side, and, as he approached Mr Shallow, with extended digits and a rolling swagger, he had a far more independent air than many a gentleman with ten thousand a year.

* * *

He was a well-made man, possessing strongly knit thews and sinews. His broad and ample chest was made the most of by a coat and waistcoat thrown back to the utmost of their capacities, and, although they caused an appearance of his having lately been exposed to some strong gusts of wind in his front, set off the proportions of his frame to some advantage.

His hair was light, and his thickly-grown whiskers — much resembling those of the Marquis in shape — were of that doubtful hue called auburn by friendly tongues, and red by inimical. The costume was certainly of the order called singular, consisting of a sky-blue broad-skirted coat with large gilt buttons, a crimson velvet waistcoat, a violet satin scarf, sticking out like the inflated crop of a pigeon, and canary-coloured, tight-fitting trousers.

There was an undeniable expression of good humour and self-satisfaction in his features, which, if not very prepossessing, were anything but the reverse; and, altogether, the Earl of Chesterlane, for it was he in propria. persona, was a man not to be passed in a crowd without the observation of observers.

I have an original copy of this tome and the best part of it is the illustration plates by George Standfast. I particularly like the one of the Count/Marquis in the dressing room of a ballerina. Indeed, for many of the personages lampooned in the book, it wasn’t an opprobrium, but a “succes de scandale.” For those interested, paperback facsimiles can be had on book e-tailers and Archive.org.