What does the dandy do when he wakes up early in the afternoon? Does he moon over beauty and contemplate the eternal verities? Does he jot down a few bons mots? Does he man the barricades to protest our vulgar, bourgeois and consumerist society? Does he pine for the days when men wore knee breeches and silk stockings?

No, the true dandy does none of these things.

The dandy goes to his bath and scrubs himself clean, shaves, brushes his teeth, and arranges any stray hairs. Then he adorns himself, examining each detail in his mirror – the dimple in his tie, the shine on his shoes, the puff of his pocket square, the precision of his trouser crease, the bloom of his boutonniere, the harmony and balance of all the components of his ensemble — until he gets it just right. When he finally departs his home, he is a habitue not of the salon, opera, theatre, museum, concert hall, casino, restaurant or club to which he may or may not arrive, but of his tailor and haberdasher.

For the dandy is a man with visible good taste. Dressing well is his hallmark. Strip a dandy of his clothes and what do you have?

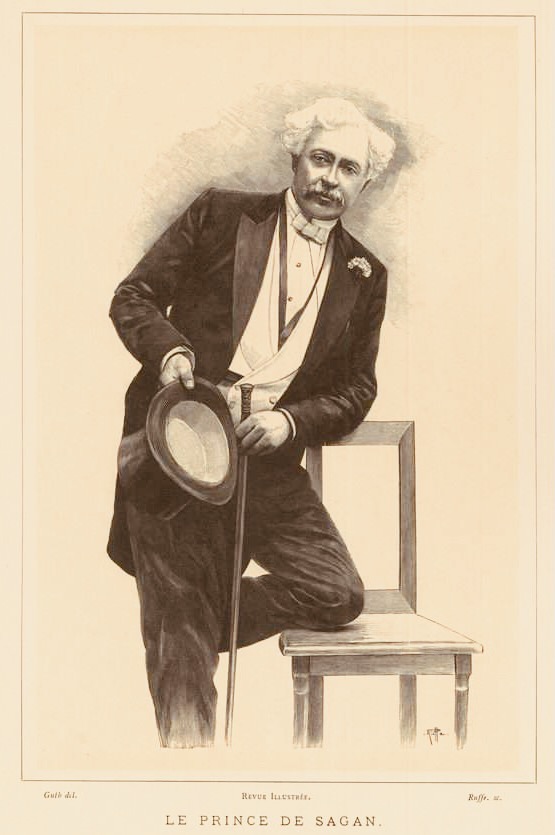

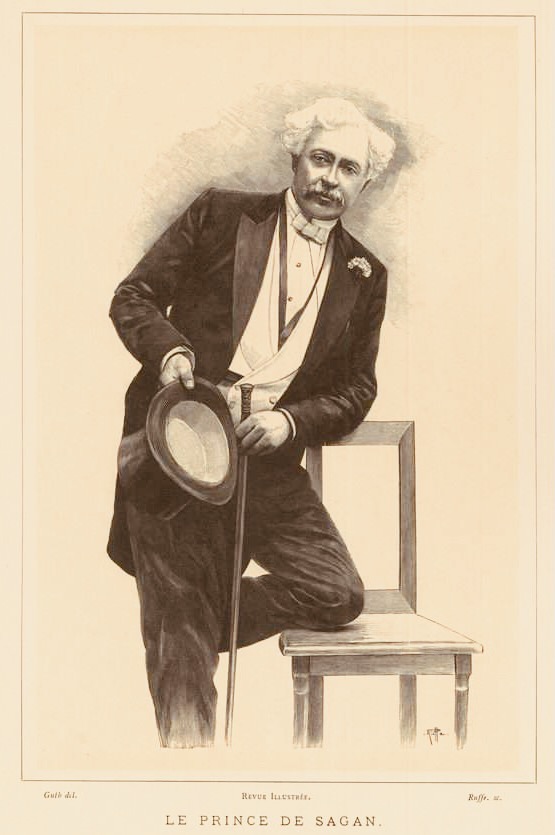

The dandy’s two-hundred-year history can be summarized in just two albeit Proustian sentences: The definitive study of the dandy as a social and literary phenomenon, Ellen Moers’ “The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm,” shows how the original, robust, snuff-snorting Regency dandy eschewed the jewel buttons, lace ruffles, silk stockings, gold shoe buckles, perfume and other extravagances of the aristocratic fop, and also the coarse slovenliness, dirt and disarray affected by republican sympathizers, and instead emphasized superb fit, perfection of cut, harmony of color, personal cleanliness and, most famously, the well-tied starched linen cravat, and came to dominate his society through his insolence, then crossed the Channel to France and returned accessorized and sissified in his attire, and became, while remaining a social lion, the more flamboyant “butterfly dandy” who eventually drank too much absinthe, smoked too much hash, raged against the bourgeois, dressed in black, and thus became the decadent dandy, who spiced his personality with wit and aestheticism, was often gay, consciously adopted aesthetic garb, entertained the mass public and thereby became the fin-de-siecle dandy, who floundered in the shallows of his own shallowness and became the extinct dandy when Beerbohm, Brummell’s true heir and most insightful interpreter, retired prematurely to Rapallo. The dandy, others might add, rose again from the dead after the carnage of the Great War and became the Bright Young Thing of the ’20s and the charming personages depicted in “Brideshead Revisited,” transfigured into the Duke of Windsor and Fred Astaire, who fashioned and embodied the guiding principle of men’s attire, nonchalant elegance, that has endured for the past eighty years, and so on to the consummate, though invisible, dandies of Dandyism.net.

But throughout the dandy’s many mutations, one constant has persisted: a dandy distinguishes himself by the way he dresses. Everything else about the dandy has been more or less mutable.

Consider, for example, the dandy as a social phenomenon. His position in, and relationship to, society has changed. The Regency dandy was a leader of society. Likewise, the social butterfly dandy was a lion of the bon ton. The decadent dandy, however, placed himself outside, rather than at the apex of, society; he was a critic of a society that had become bland and conformist. The fin-de-siecle dandy also was a critic, this time of Victorian values.

Indeed, the dandy’s social significance was sometimes contradictory. Take again the Regency dandy. For the common-born Regency dandy such as Brummell, dandyism was a way to join the aristocracy, often while mocking its foibles. For the aristocratic Regency dandy, such as Wellington, it was a way to justify one’s superior position and affirm the legitimacy of the aristocracy when it was under attack.

Either way, the Regency dandy had to assert himself in an exclusive, elitist, stratified society. Today’s society is, in contrast, is mass, consumerist and democratic. We build, as Tom Wolfe has noted, Las Vegas, not Versailles. Therefore, aping the manners of 19th-century dandies would be as inappropriate for a contemporary dandy as dressing up in 19th-century costume.Here Beerbohm’s observation is spot on: “The dandy is the ‘child of his age,’ and his best work must be produced in accord with the age’s natural influence. The true dandy must always love contemporary costume.”

Moreover, the “philosophy” of the dandy attributed to him by most scholars is really no way to go through life. Irony is a literary device, not a way of life, and detachment is a waste of a life. In Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time,” the narrator rhetorically asks of the detached Charles Swann, “For what other lifetime was he reserving the moment when he would at last say seriously what he thought of things, formulate opinions that he did not have to put between quotation marks, and no longer indulge with punctilious politeness in occupations [that] he declared at the time to be ridiculous?”

Indeed, for what other lifetime? These attitudes are simply not worth adopting and there is no need to do so in order to be a dandy. Again, as Beerbohm cautioned, “There is no reason why dandyism should be confused, as it has been by nearly all writers, with mere social life. Its contact with social life is, indeed, but one of the accidents of an art.” That art is wearing clothes artfully and well.

There are those who cannot accept this conclusion. They fear that emphasis on the dandy’s outward appearance reduces him to some vulgar swank. They are not content with the dandy’s own choice of ensemble. They must robe him with a regal mantle. His outward elegance reflects some inner nobility, they say. Romantic twaddle, I say.

I blame, in the words of Sir Percy Blakney, those demmed Frenchies. Instead of being dandies they analyzed dandyism. Barbey, I believe, was a real dandy. Baudelaire, with his black wardrobe, I am not so sure of. Balzac wrote perceptively and wittily about the dandy’s life in his fiction and penned “La Traite de la Vie Elegante,” an ostensibly anti-dandy tract full of valid sartorial epigrams. Yet Balzac was, by all accounts, oily, fat and dirty, and therefore no dandy. The French thereby started the process of disassociating the dandy from his clothes, thus obscuring his essence. Not only that, these hierophants of dandyism provided grist for academic mills to belch wearisome dissertations in comparative literature and gender studies in pursuit of advanced degrees and often in furtherance of certain social and political agendas.

“The English invented dandyism, the French explained it,” George Walden recently wrote. I say that a dandy needs no explanation, no justification, no interpretation. Instead of analyzing the dandy, we must return to the dandy’s Regency roots and directly experience with our senses the luminosity of dandyism itself.

If you must coat the dandy with some intellectual veneer, then think of him as an existential hero. In response to our mass, abstract, anonymous, and impersonal society, he asserts his singular self. And, in dandyism’s grand tradition, he chooses to assert his superiority in the most frivolous manner possible.

I prefer to think of the dandy as a lily of the field. The Bible reads, “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin. And yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.”

So, dear reader, purge yourselves of philosophical pretensions, emulate the lilies of the field, and ponder life’s most important question: What will you wear? — NICK WILLARD

You forget, esteemed colleague, that there is one other factor common to the dandy’s genus: confidence.

The sniveling little turds in their tuxedo-print tees, false ray-bans and sausage-casing suspended-jeans who have so recently emerged from mildewed studio floorboards or picket-fenced organic-soy gardens to mar my parks and ruin my strolls may be what passes for ‘hip’ today, but they can never be known as dandies. The idea would be absurd not because they do not dress well, but because they lack the confidence to even think they dress well.

I have yet to see a hipster male carry himself with poise, or elegance, or decent posture. The same goes for any man who lets his wife dress him or who follows the dictates of the fashion rags as if all suggestions were law.

With confidence comes composure, a care for detail and the ability to make one’s tailor rather than letting oneself be made by him. Without this crucial attribute I fear that before long anybody with enough money to hire a good fashion stylist will be considered a dandy. In other words, it is not enough for a dandy to know what he is wearing, he must also be proud to be wearing it.

Your all insane. Dandyism is dead.

So is diction.

I am very much in agreement with Mr. Rich and Mr. Willard.

I agree with Rich completely.

But I also wonder, what of the female dandy?

Very very sadly, there can be no female dandies.

There simply never has been. There’d be no point to it — no joyous culture-shock. Women have been raised in society to get dolled up every day.

We’re here as muses for the dandies.

I know female dandies, Rachel.

Come to Madrid, and I will show you my Salon.

E.T. de Ribes

Directed mainly at Rich:

I always thought a dandy was someone who appreciating style and was a trendsetter, I admit I do not particularly care for false rayban wearing ‘hipsters’ but you speak of them with such disdain and snobbery that you are much worse than them.

A dandy should appreciate new styles and movements and not hold onto their own personal bias like a leech. To speak so ill of such people, who often are not rich and are merely trying to resemble what is considered stylish (much like dandies did originally in Britain), shows that you contain not of the qualities that you yourself say a dandy requires. Your language lacks composure, confidence and elegance and is simply hypocritical

My Name is Jack R. Dandy……..My uncle is named James N. Dandy

Dandyism is alive and well…..without knowing one single fact about Dandyism and for that matter I, by some luck only stumbled onto Dandyism and after reading the good and the bad about this strange ism…..I confer to you ladies and gentlemen that I act, dress, and interact like a true Dandy from that time of true dandyism, so long ago……

Amazing find for me …

Thank you all for your comments

Jack R. Dandy

I’m a little confused. You seem to assert that Dandyism is nothing but wearing clothes well, but then you also suggest a Dandy is an “existential hero”. It seems odd that on a site devoted to Dandyism you are not prepared to make any distinction between a Dandy and one who simply dresses nicely. Surely the notion of Dandyism, whatever its roots, must represent a specific philosophy, and dressing well is only one of its manifestations. Perhaps you are expressing your own philosophy: it’s good to dress well for its own sake. However, I can assure you it falls far short of my own. Your analysis demonstrates the distinct lack of self-awareness and self-analysis that is responsible for the unsatisfying behaviour and attitudes of the common masses, and self-awareness and self-analysis are an essential aspect of Dandyism.

Tony, The second hallmark of a dandy, after his appearance, is not to take these things too seriously.

…as the church is for the blood of Christ, so is the d. for the clothes. He redeems it through his love, attention and everyday’s little rites.

I have been reading your site with great interest and merriment, however, I do have a question for you though: Does a ‘failed’ Dandy just become a ‘Chap’. I have to say that I failed the test on how dandy I am on your, rather informative, website, but I do conform to everything in the third paragraph of the above article, along with most of the other observations that have been made.

I have always subscribed to ‘Chappishness’ wherever possible such as doffing ones hat to a lady, wearing tweed (after all, no other fabric says so defiantly: I am a man of panache, savoir-faire and devil-may-care, and I will not be served Continental lager beer under any circumstances.) and the never fastening the lower button of ones waistcoat goes without saying. This one dates back to Edward VII, sufficient reason in itself to observe it.

I would just like to finish by saying do please keep up the good work.

Sterling effort by all involved!