It’s not often one happens upon a gem in the papers, especially one with something poignant and propitious to say about the body dandiacal. Well, at least not in the papers these days, anyway.

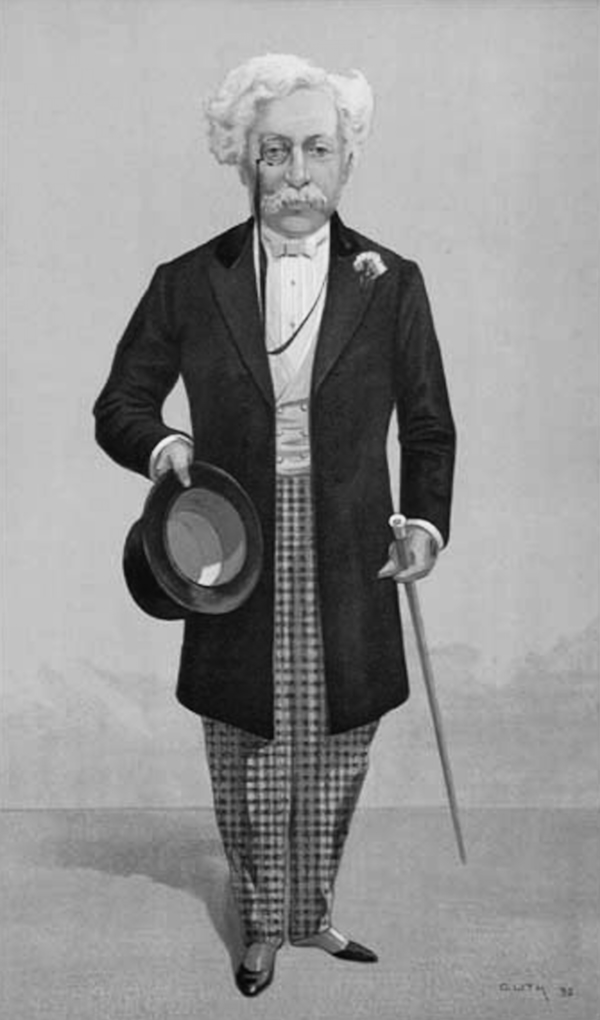

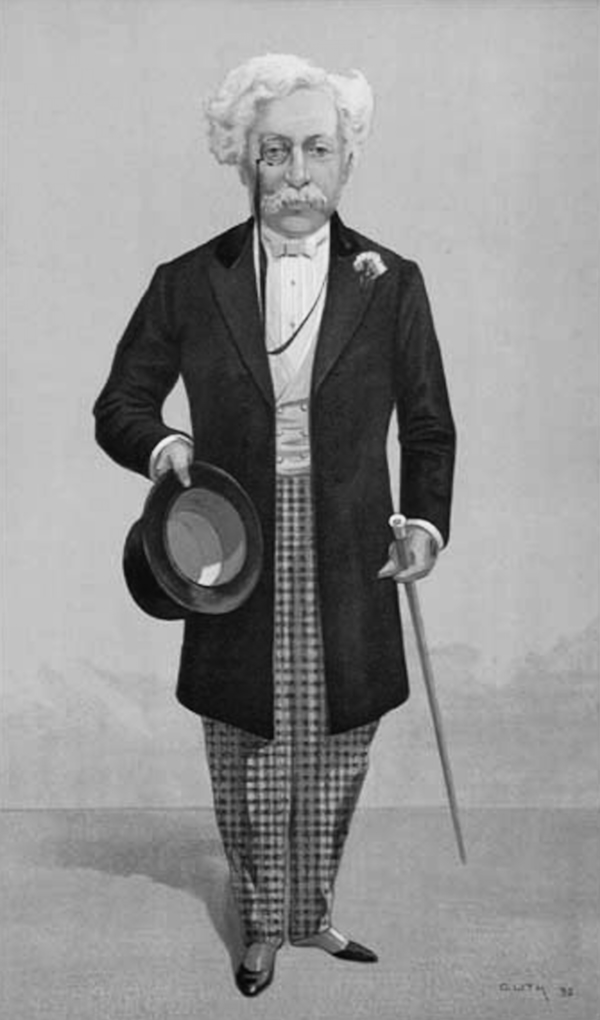

So we were pleased to stumble across, via a blog called The Esoteric Curiosa, a 1910 appreciation out of The New York Times of Charles Guillaume Frederic Boson de Talleyrand-Perigord, more commonly known as the Prince de Sagan. Born in 1832, Talleyrand-Perigord grew up to become a cavalry officer. That in itself is unremarkable, though it is telling. Like many a future dandy, Talleyrand-Perigord was an officer of horse, which, unlike the navy, the courts or the clergy, affords the kind of exercise that makes for a well-turned leg while avoiding the drudgery of the infantry.

One cannot say that Talleyrand-Perigord, who became Duc de Sagan in 1845, rose to anything. He was born on high though in a country subject to constant (and sometimes deadly) revolution and change. Rather, he became the arbiter elegantarium of Parisian capital S Society and its demi-monde through the power of style. As the anonymous author of the Times article writes:

It was the sovereignty of fashion — that is to say, of fashion in the broadest sense of the word, and in which the mere question of clothes played a very small part. He was no mere Beau Brummell, but rather an Alcibiades, in this sense, that he dictated the tastes, the prejudices, the fads, and the crazes of the hour. And not content with setting the fashion, he made people fashionable, for a briefer or a longer period, according to his caprice and his interest.

But what most interested us about the article was its almost Beerbohm-like discourse on what it means to be a dandy, to be a classically attired man and yet chic at the same time:

Perhaps I can best convey an idea of the role which he played by calling attention to the title conceded to him by his countrymen, namely, that of “Le Roi Du Chic.” Of course, the question will be asked as to just what “chic” means. Webster tells us that it stands for “good form” and “style,” which, with all due reverence to so eminent an authority, is an inadequate definition. At Vienna, at Berlin, also here in New York, it serves to describe articles of raiment that savor of the grand couturiers at Paris, rather than of the native modistes, while in London it is not only used in the same sense, but also as a synonym for the terms “smart” and “swagger.”

What “chic,” however, really means is not so much “style,” “form,” nor “fashion,” so called, as originality, combined with correct taste, and a complete absence of affectation. One of the best living illustrations of the word “chic” is Princess Pauline Metternich. She is “chic” to the tips of her fingers, in thought, speech, dress, manner, conduct, and appearance. She is “chic” because she is so original, unaffected, and yet so tasteful in everything that she does. Those who endeavor, with varying success, to imitate her, are not “chic.” Indeed, no persons who follow a fashion, or who seek to shape their way in accordance with those of any particular sample or model, can lay claim to that qualification. In order to possess chic it is necessary to have a well defined individuality, with qualities, aye, and defects as well, that are peculiarly one’ own.

Sadly, though like many of his predecessors — those masculine purveyors chic — Le Duc eventually lost his marbles, probably due to syphilis, and passed away a prisoner to an uncaring monde. — D.NET STAFF