From “New Notes On Edgar Poe,” 1857

By Charles Baudelaire

Decadent literature! Empty words which we often hear fall, with thes onority of a deep yawn, from the mouths of those unenigmatic sphinxes who keep watch before the sacred doors of classical Aesthetics. Each time that the irrefutable oracle resounds, one can be sure that it is about a work more amusing than the Iliad. It is evidently a question of a poem or of a novel, all of whose parts are skillfully designed for surprise, whose style is magnificently embellished, where all the resources of language and prosody are utilized by an impeccable hand.

The phrase decadent literature implies that there is a scale of literatures, an infantile, a childish, an adolescent, etc. This term, in other words, supposes something fatal and providential, like an ineluctable decree; and it is altogether unfair to reproach us for fulfilling the mysterious law. All that I can understand in this academic phrase is that it is shameful to obey this law with pleasure and that we are guilty to rejoice in our destiny.

The sun, which a few hours ago overwhelmed everything with its direct white light, is soon going to flood the western horizon with variegated colors. In the play of light of the dying sun certain poetic spirits will find new delights; they will discover there dazzling colonnades, cascades of molten metal, paradises of fire, a sad splendor, the pleasure of regret, all the magic of dreams, all the memories of opium. And indeed the sunset will appear to them like the marvelous allegory of a soul filled with life which descends behind the horizon with a magnificent store of thoughts and dreams.

But what the narrow-minded professors have not realized is that, in the movement of life, there may occur some complication, some combination quite unforeseen by their schoolboy wisdom. And then their inadequate language fails, as in the case — a phenomenon which perhaps will increase with variants — of a nation which begins with decadence and thus starts where others end.

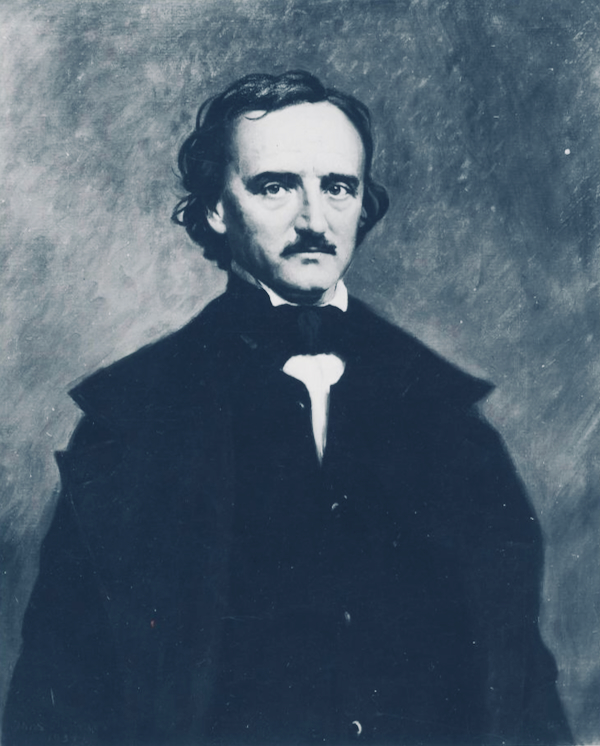

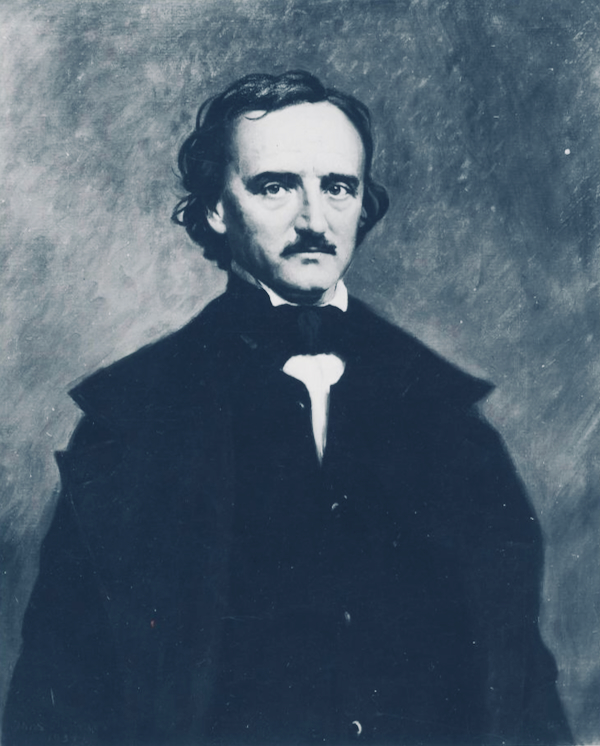

Aristocrat by nature even more than by birth, the Virginian, the Southerner, the Byron gone astray in a bad world, has always kept his philosophic impassibility and, whether he defines the nose of the mob, whether he mocks the fabricators of religions, whether he scoffs at libraries, he remains what the true poet was and always will be-a truth clothed in a strange manner, an apparent paradox, who does not wish to be elbowed by the crowd and who runs to the far east when the fireworks go off in the west.

But more important than anything else: this author, product of a century infatuated with itself, child of a nation more infatuated with itself than any other, has clearly seen, has imperturbably affirmed the natural wickedness of man. There is in man, he says, a mysterious force which modern philosophy does not wish to take into consideration; nevertheless, without this nameless force, without this primordial bent, a host of human actions will remain unexplained, inexplicable. These actions are attractive only because they are bad or dangerous; they possess the fascination of the abyss.

This primitive, irresistible force is natural Perversity, which makes man constantly and simultaneously a murderer and a suicide, an assassin and a hangman — for he adds, with a remarkably satanic subtlety, the impossibility of finding an adequate rational motive for certain wicked and perilous actions could lead us to consider them as the result of the suggestions of the Devil, if experience and history did not teach us that God often draws from them the establishment of order and the punishment of scoundrels; after having used the same scoundrels as accomplices!

Such is the thought which; I confess, slips into my mind, an implication as inevitable as it is perfidious. But for the present I wish to consider only the great forgotten truth — the primordial perversity of man — and it is not without a certain satisfaction that I see some vestiges of ancient wisdom return to us from a country from which we did not expect them. It is pleasant to know that some fragments of an old truth are exploded in the faces of all these obsequious flatterers of humanity, of all these humbugs and quacks who repeat in every possible tone of voice: “I am born good, and you too, and al of us are born good!” forgetting, no! pretending to forget, like misguided equalitarians, that we are all born marked for evil!

Progress, that great heresy of decay, likewise could not escape Poe. The reader will see in different passages what terms he used to characterize it. One could truly say, considering the fervor that he expends, that he had to vent his spleen on it, as on a public nuisance or as on a pest in the street. How he would have laughed, with the poet’s scornful laush, which alienates simpletons, had he happened, as I did, upon this wonderful statement which reminds one of the ridiculous and deliberate absurdities of clowns. I discovered it treacherously blazoned in an eminently serious magazine:

The unceasing progress of science has very recently made possible the rediscovery of the lost and long sought secret of Greek fire, the tempering of copper, something or other which has vanished, of which the most successful applications date back to a barbarous and very old period!!!

That is a sentence which can be called a real find, a brilliant discovery, even in a century of unceasing progress; but I believe that the mummy Allamistakeo would not have failed to ask with a gentle and discreet tone of superiority, if it were also thanks to unceasing progress — to the fatal, irresistible law of progress — that this famous secret had been lost.

If one wishes to compare modern man, civilized man, with the savage, or rather a so-called civilized nation with a so-called savage nation, that is to say one deprived of all the ingenious inventions which make heroism unnecessary, who does not see that all honor goes to the savage? By his nature, by very necessity itself, he is encyclopedic, while civilized man finds himself confined to the infinitely small regions of specialization. Civilized man invents the philosophy of progress to console himself for his abdication and for his downfall, whereas the savage man, redoubtable and respected husband, warrior forced to personal bravery, poet in the melancholy hours when the setting sun inspires songs of the past and of his forefathers, skirts more closely the edge of the ideal.

Of what lack shall we dare accuse him? He has the priest, he has the magician and the doctor. What am I saying? He has the dandy, supreme incamation of the idea of the beautiful given expression in material life, he who dictates form and governs manners. His clothing, his adorments, his weapons, his pipe give proof of an inventive faculty which for a long time has deserted us.

Such an environment — although I have already said so, I cannot resist the desire to repeat it — is hardly made for poets. What a French mind, even the most democratic, understands by a State, would find no place in an American mind. For every intellect of the old world, a political State has a center of movement which is its brain and its sun, old and glorious memories, long poetic and military annals, an aristocracy to which poverty, daughter of revolutions, can add only a paradoxical luster; but That! that mob of buyers and sellers, that nameless creature, that headless monster, that outcast on the other side of the ocean, you call that a State?

I agree, if a vast tavern where the customer crowds in and conducts his business on dirty tables, amid the din of coarse speech, can be compared to a salon, to what we formerly called a salon, a republic of the mind presided over by beauty!