A 19th-century woman wrote herself into the annals of history by saying that the feeling of being perfectly well dressed brings a supernatural calm that not even religion can bestow. But can vestments really hold such power, and is there a deeper link between sartorial finery and transcendent states of being? There is, and a flamboyant but staunch Catholic was a herald of dandyism, the modern world’s most fascinating philosophy of elegance.

Entering the lexicon in the 18th century — the song “Yankee Doodle Dandy” is about Americans mocking British foppery — the term dandy coincides with the rise of George Bryan Brummell, nickname Beau, considered the first celebrity, or man famous for simply being famous. This fame, which was much closer to notoriety, resonated throughout Regency England for its combination of a cold demeanor, way of speaking highly of trivial matters and casually of serioius matters that conveyed a sense of tragicomic detachment, and innovations in dress that essentially created the blueprint for the sober elegance of polished black footwear, navy coat, white shirt, and perfectly knotted neckwear men still wear today.

But the transformation from “dandy,” denoting a socially prominent man of elegance and wit, to “dandyism,” a philosophy of life with transcendent connotations, owes itself to Jules Amadeé Barbey d’Aurevilly, who saw in the figure of Brummell a man “who bears within him something superior to the visible world,” led by “an air of elegant indifference which he wore like armor, and which made him invulnerable,” and with so peculiar a personality it must surely reveal “the finger of God acting through the intelligence.”

Since men and women need the opposite sex to help understand themselves, one of Barbey’s most astute interpreters is historian Ellen Moers, author of the 1960 study “The Dandy.” Her chapter on the “eccentric, romantic, Bohemian, Catholic and dandy” that is Barbey d’Aurevilly recounts the writer’s early days when literary poverty necessitated that “his dandyism was restricted to the spirit.” Indeed, when he sought to supplement his income with articles for the fashion periodical Le Moniteur de la mode, the editors found his work too “metaphysical.”

Determined to explore the link between the sartorial and the sacerdotal, Barbey self-published his hagiography “On Dandyism and George Brummell” in 1844, where he asserted that, as Moers puts it, dandyism was “a spiritual achievement of considerable dimensions,” and “an attitude of protest against the vulgarized, materialistic civiliation of the bourgeois century.” Hagiography is indeed not too much of an exagerration, for, as Moers writes, “How far indeed from George Bryan Brummell is Barbey’s definition of the dandy as a holy man.” She goes on to say, “In its hostility to the bourgeois ethic and to romantic liberalism, dandyism was in part a complement and in part an alternative to the Catholic revival. In its insistence on order and ritual and discipline, in its disdain for enthusiasms and entanglements, the dandy pose had much to commend it to the intellecutal Catholic.”

It was Barbey who noted that poet Charles Baudelaire’s primary concern was religious values — and their rapid disappearance — and in a case of kindred spirits and strange rapport, Baudelaire — who’s considered the godfather of Modernism — also succumbed to the lure of dandyism as a stance of elegant aloofness and protest against the doctrine of egalitarianism. Although his contribution to dandy lore is much shorter — just a brief essay published in 1863 — its language is far more imaginative, and continues to inspire radicals and reactionaries alike. No longer merely human and social, nor even a philosophical temperament, dandyism in the mind of Baudelaire shows a form of spiritual asceticism arrived at the sunset of civilization, when all values are beginning to become materialist and collectivist.

The dandy does not stand before the march of progress yelling stop only to be run over by the stampeding masses, and instead retreats to his innermost core, establishing an aristocratic code of conduct pulled down from the stars. Extracting the essay’s most pregnant passages, we get an esoteric doctrine that goes something like this:

Dandyism is a kind of aristocracy difficult to break down because it is founded on indestructible divine gifts.

It is a doctrine, a monastic rule, a rigorous code to which certain disenchanted outsiders are strictly bound. Dandyism is a strange form of spirituality, almost a religion, fueled by a burning desire to create oneself, and stemming from an aristocratic superiority of mind.

Fueled by a latent fire, the dandy’s native energy is the source of his haughty, patrician attitude, aggressive even in its coldness.

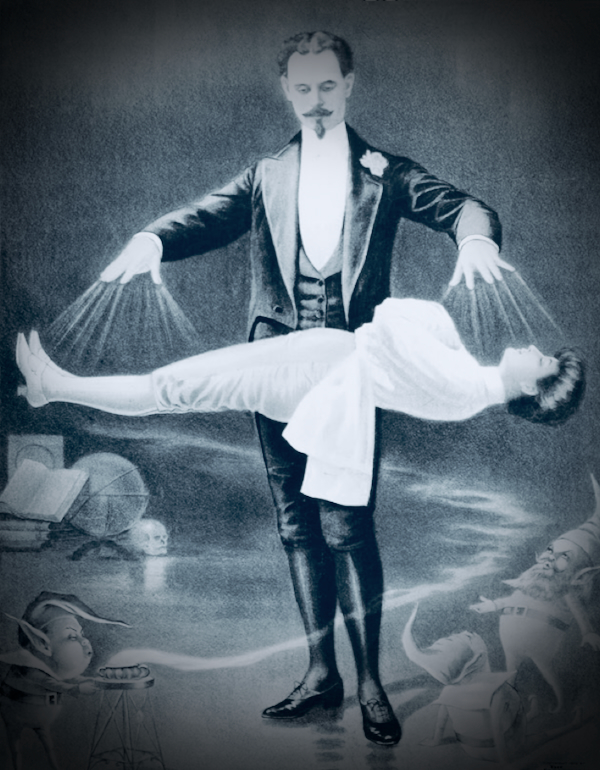

Dandyism strengthens the will and schools the soul, bestowing a calmness revealing strength through risky sporting feats and a flawless dress of elegance and distinction.

The dandy is a champion of pride who destroys triviality through opposition and revolt.

Dandyism is a setting sun, magnificent and full of melancholy. It is the last flicker of heroism in decadent ages, when democracy and egalitarianism are not yet all-powerful.

Baudelaire lent his spiritual theories to feminine elegance as well, advocating for what in the 20th century would come to be known as glamor. In his essay “In Praise of Make-Up,” also from 1863, the poet-aesthete views cosmetics not as a falsifying of nature, but rather a spiritual aspiration to a plane high above the natural that lords over the imagination in the form of the ideal. Fine dress, he writes, “is one of the signs of the primitive nobility of the human soul” valued by those who have “received at birth a spark of that sacred fire they use to illuminate their whole being.” Fashion and cosmetics create “a magical and supernatural appearance,” and face powder, like skin-tight leggings, “imemdiately renders the human being like a statue, that is to say, like a divine and superior being,” while black eyeliner frames the whites of the eye and makes it seem like “a window open on infinity.”

Returning to masculine elegance, Baudelaire’s doctrine of dandyism can be seen a final expression of the heroic spiritual path of chivalry, which combined feats of courage and martial skill — Baudelaire’s “risky sporting feats” — with courtly graces. Winding back through time, Medieval chivalry intersects with the Ars Regia, or sacred science of alchemy, and from there to the Primordial Tradition and mankind’s original archetypal unity. The so-called Royal Art’s supreme symbol is that of the rebis, Latin for “double thing,” a hermaphroditic figure symbolizing the restoration of the primordial state, the original double-sexed archetype of the human being created in God’s image, with the Eve principle restored to its place in Adam’s rib from which it was extracted during incarnation and the division of the sexes.

Indeed Barbey d’Aurevilly ends his book with the observation that dandies are “Twofold and multiple natures, of an undecidely intellectual sex, their Grace is heightened by their Power, their Power by their Grace; they are the hermaphrodites of History, not of Fable.” And so a tradition that began with Beau Brummell, which at its least was selfish frivolity and at its best staunch independence in the face of empire and revolution, became transformed into a modern metaphysical path in the imagination of the two Frenchmen Barbey and Baudelaire, providing a newly forged path up an ancient mountain, one that permits those rare few driven by an undaunted will to claim their God-given regal dignity.

Our place on the timeline of history makes one thing crystal clear, and that is that — alongside chaos over order, falsehood over truth, and the material over the spirit — the Devil loves ugliness. He loves dehumanizing buildings, nihilistic music, and apathetic attire. In ages less sartorially bleak, there were sumptuary laws regulating how a person could dress in public. Though intended to protect those of low caste from disguising themselves for nefarious purposes, today we can take inspiration from this concept and beat the Devil at his own game with a sly act of inversion.

Think of it as a reverse sumptuary law one follows to avoid being taken not for one above, but rather below. Let those whose heart burns with the flame of the spirit adorn themselves in such a way that they are never mistaken for the godless ones who know not the Good, True and Beautiful, and who wander blind through the netherworld of contemporary life. And let us hope that our attire inspires them to begin to see, and to raise their standards in everything they do — including dressing themselves in the morning — towards that celestial realm where the ideal reigns in supernatural poise. — CHRISTIAN CHENSVOLD