“La chair est triste, helas, et j’ai lu tous les livres.” When I was younger, those lines of Mallarmé used to haunt me. This was back when I could tolerate Mallarmé’s deliberate obfuscations. These days I take my whisky straight, and prefer the direct approach of AE Housman.

But recently that line resurfaced in my mind, and while I’m quite sure my flesh is sad, I began to wonder if I really had read all the books. Sure, I tear through non-fiction, and there’s the constant speed-reading of magazines and websites, but I can’t remember the last novel to capture me the way they did in my twenties, when the world was new and each tome seemed to offer greater insight into myself and my path in life. Finding a suitable work of literature became an exercise in dandyish discrimination in which nothing suited my taste. Was I really destined to just reread Stendhal’s “Red and the Black,” Balzac’s “Lost Illusions,” and Flaubert’s “Sentimental Education” for the rest of my life?

Then the opera began a production of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde,” and in preparation I picked up my collegiate copy of the stories of Thomas Mann, intending to reread one called “Tristan.” Sure enough, after two pages I came down with an instant case of dandy ennui. I was about to put the book away, then noticed there was a story in the collection entitled “The Joker” which I didn’t recall having ever read. As I delved in, it became clear why I’ve been so blasé about reading for the last 10 years: I’d strayed away from dandy lit.

Yes, “The Joker,” written in 1897, was a hit. So allow me, faithful myrmidons, to tell you a dandy bedtime story.

Our unnamed first-person narrator (let’s call him J) is a young, idle dilettante. After receiving a small inheritance, he embarks on a life of leisure, “doing exactly as I pleased: reading good, elegantly written novels, going to the theater, playing the piano a little.” J admits he is “an absolutely useless individual.” He is also a chronic overspender, who takes an elaborate pleasure in furnishing his apartment, where he plans to live in “carefree independence” and “untroubled, contemplative leisure.” Since he’s not rich, J spends as little as possible on daily necessities in order to afford aesthetic indulgences, such as opera tickets. His sense of natural superiority grows as he sees nothing but mediocrity around him. “I liked playing the charmer,” he says, “though instinctively I was beginning to despise all these prosaic unimaginative people.” And later, “… my eyes sparkling with high-spirited mockery and an air of benevolent superiority to everyone…”

As presented in Dandyism.net’s definitive guide to the dandy personality, “Anatomy of the Dandy,” sartorial elegance must be part of the formula, and sure enough J is a leader of fashion:

I wore the best clothes, and even when I was younger and still at school I had noticed how my poorer and shabbiily dressed contemporaries habitually deferred to me and to others like me, treating us with a kind of flattering diffidence which indicated their willing aceptance of us as lords and leaders of fashion.

Now here’s my favorite part about J: He’s classless. As a dandy outcast, J doesn’t fit in any readily formed social sphere. Though educated and a man of leisure, he has no prominent social connections. As for literary cafe society, J says:

I wear clean linen and a decent suit, am I supposed to enjoy sitting with unkempt young men around tables sticky with absinthe, discussing anarchism?

Simply being a dandy is enough of a tragic flaw, but J’s is more specific. He says at one point, “It was very gratifying to live as a rather alien, effortlessly superior figure among these acquaintances and relations of mine whose limited outlook I found so amusing, but to whom, because I liked to be liked, I behaved with adroit charm.” Herein, no doubt, lies J’s fatal flaw: There is no room in Dandyland for needing to be liked. And when J becomes infatuated with a young lady, her more appealing suitor throws J’s ordered existence into chaos.

Mann was fond of doppelganger figures, and J’s rival is a shadowy reflection of himself. Dr. Witznagel is a more polished and handsome version of J, at the center of society rather than aloof from it, and possessing “the most incomparable shirtfront I have ever in my life been privileged to see.” It is dandy-as-reclusive aesthete versus dandy-as-society lion. Witznagel moves with an air of assurance. When conversation lags, “he would relapse into profound contemplation of both points of his moustache.” When conversation rekindles, Witznagel would “smile a shade patronizingly down at his young neighbor. There could be no doubt that this gentleman rejoiced in a wonderfully happy conceit of himself.” J appreciates this in the man, and calls the nonchalance of Witznagel’s movements “a trifle daring.” J writes:

Here clearly was a man who, while perhaps lacking any particular distinction, had irreproachably made his way, and would pursue it to clear and profitable ends; who sheltered in the shade of agreement with all men, and basked in the sunshine of their general approval.

Compared to such a truly superior being, J feels pitiful. And when marriage is announced between Witznagel and J’s secret crush, J feels “doomed.” I leave you to savor the denouement on your own. But I must caution you that dandy bedtime stories, like life, usually end with the hero living unhappily ever after. — CC

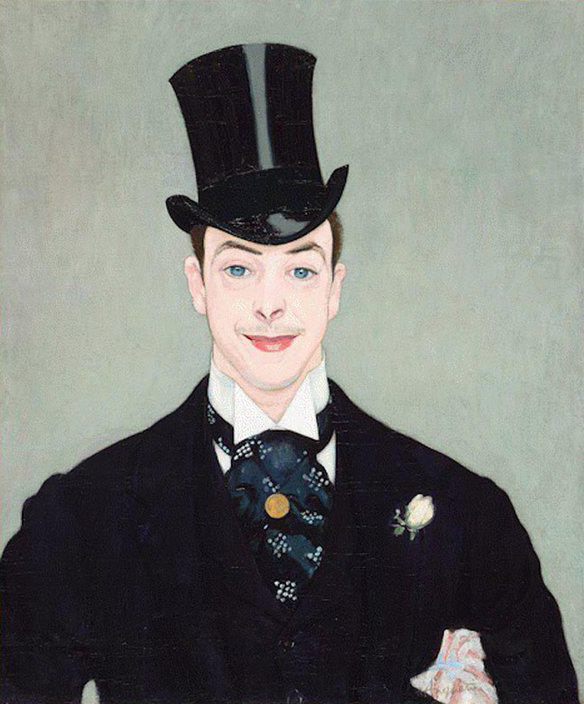

Image: “Henri Samary” by Louis Anquetin, 1890.

Good one, post and image.