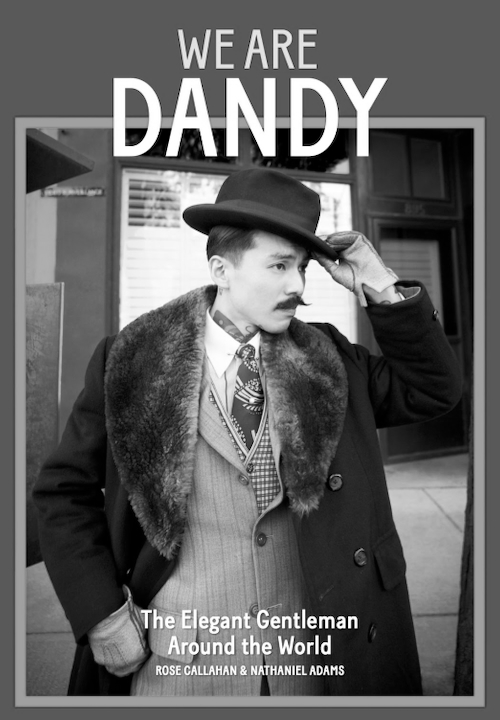

I most heartily recommend you rush out and purchase Natty Adams and Rose Callahan’s collaboration, “We Are Dandy: The Elegant Gentleman Around the World.” Their follow-up to 2013’s “I Am Dandy” introduces another 60 dandies of various stripes from around the world. The book opens with a charming preface by noted ecdysiast Dita von Teese, in which she assures us, in so many words, that she goes down for dandies. It is unclear if her professed proneness represents an exception or the rule. Then comes Rose’s beautiful photographs and Natty’s far-from-prosaic prose. Rose captures each dandy in situ and in the wild, such as a rented palazzo in Florence and an Art Deco Tokyo hotel room available at reasonable day rates. Complementing Rose’s picture-pictures are Natty’s word-pictures that capture each subject’s individuality and his singular take on the meaning of dandyism.

Most interestingly, this time Natty’s introduction does not contain a warning, as his introduction to “I Am Dandy” notoriously did, that a substantial but undisclosed number of the book’s subjects are not actual dandies, but only dandies manqué, and in some instances not dandies at all. The absence of such a caveat in this volume impliedly vouches that all the denizens of “We Are Dandy” are, in fact, real dandies, which is most reassuring to persons who take things literally, such as myself.

Natty, a scholar of dandyism as well as a dandy himself (he was, as we are never loth to boast, Dandyism.net’s 2013 Dandy of the Year), goes on to identify the precisely four varieties of dandies: the vintage dandy, the classicist, the #menswear dandy, and the fashion dandy. He then deftly limns their dominant characteristics. His taxonomy is vastly superior to previous efforts at dandy classification, such as the Whimsy Bohemian-Dandy Class Continuum diagram of 2006. His taxonomy, as insightful as it is, glosses over, however, a deeper, more fundamental dichotomy plaguing dandyism, a division that threatens to rent the fabric of the dandysphere. I speak, of course, of the incipient dandy civil war being instigated by Mr. Logan O’Malley of Brussels, Belgium, and Mr. Justin Fornal of Yonkers, New York. Separated by 3,200 miles, both dandies lay claim to the title of Baron of Dandyism.

Mr. O’Malley, who, we are told, is generally known among the Brussels lumpenproletariat as “Le Baron,” refers to himself as “Clyde Baron de Frenchteush, etc. etc. ad infinitum.” He explains, “The baron is the dandy of the street. The baron is someone who is well dressed but very poor. ‘Baron’ is a word to refer to strong but elegant people. Everybody can be well-dressed, everyone one can be a dandy, but not everyone can be a baron.”

These last words rudely repudiate Mr. Fornal’s competing assertion of the privileges of the nobility. Mr. Fornal styles himself on public-access TV and elsewhere as Baron Ambrosia and traces the lineage of his baronetcy directly to the voodoo spirit Baron Samedi, memorably portrayed by the late Geoffrey Holder in the 1973 James Bond thriller “Live And Let Die.” This baron boasts of a formidable Praetorian Guard, no less than the Zulu Nation, a Bronx-based, old-school, hip-hop gang.

One worries whether the dandysphere is big enough to accommodate the rival claims of the House of O’Malley and the House of Fornal. Any student of American history will tell you that a house divided against itself cannot stand. Conflict appears inevitable: the two barons share little in common except for a propensity to include in their respective conversation as many declensions of the word “fuck” as possible. I fear a schism that forever cleaves dandyism in twain. This leads naturally to an even more dire threat lurking below the pretty pictures and precious descriptions of “We Are Dandy,” to the very subsistence of dandyism.

A close reading of the text reveals that the capital of dandyism has shifted from London, where Beau Brummell founded the tradition in 1796, to Tokyo and Johannesburg. Fully 12 of the dandies appearing in “We Are Dandy” live in the Japanese capital (with two more residing elsewhere on the main island of Japan), and nine dandies live in Johannesburg. No other location comes close in the number of dandies. This seismic geographic shift represents more than a personal inconvenience. I am sure that in time I could acclimate myself to Johannesburg, despite water draining out of sinks counterclockwise and blood rushing to my head because I’m standing upside-down on the bottom side of the equator (although I suppose for an old lion like myself it will take longer to figure out the proper application of the wearing white/Labor Day rule). I am similarly confident that in Tokyo I could get used to drinking sake while reading Saki.

No, what troubles the soul is that — except for an occasional montsuki, the most formal style of kimono, or hakama trousers — these dandies of Japan and Africa are attired in suits, jackets, ties, and shoes — all traditional sartorial artifacts of Western Civilization. These dandies, obviously extraneous to the Occident (except for Mr. Gene Krell, pictured above, who doesn’t look Japanese), readily concede — nay, proclaim — that their sartorial choices have been consciously influenced by cultural expressions from Western Civilization, such as American and British movies, American jazz, and Ivy Style clothing. Not one of them states that they first asked permission, and I assure you no one asked for mine. The pernicious effect of this exploitation of Western Civilization is to make the borrowers seem innovative and edgy — this is especially true of the African dandies — while perpetuating the negative, hurtful stereotype that those of European descent who wear the same items are stuffy and lacking in creativity.

Perhaps it is time to bid farewell to the Lethe-like pleasures of Oscar Wilde’s epigrams, which wittily manipulate the masses into docile contentment with repressive socio-political regimes. Perhaps it is time to say goodbye to bespoke suits, which cultivate a false psychological need for quality and craftsmanship, a need that can be satisfied only by the products of capitalism, further entrenching the dominant economic interests. Perhaps it is time, indeed, to leave behind dandyism itself. I stand, metaphorically speaking, with Matthew Arnold on Dover Beach, contemplating my loss of faith in dandyism, my John Lobbs (Paris shop) carefully toeing the Sea of Faith, within sight of the glimmering and vast cliffs of England, feeling forsaken, and wondering, silently, “O Brummell, where art thou?” — NICK WILLARD